Transition to adulthood

| Site: | ELPIDA Course |

| Course: | ELPIDA Course - English |

| Book: | Transition to adulthood |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 28 February 2026, 3:33 PM |

Table of contents

1. Introduction

Before we start, let us ask some questions of reflection

How do you think your child will behave during puberty?

How they feel during this difficult time?

How can you support your child during Transition to adulthood?

Do you know possibilities for sharing responsibilities in your child’s life?

Children grow up and everything changes. This is difficult even under "normal" circumstances, but if the child has an intellectual disability, this completely natural development is perceived as even more difficult. This process cannot be stopped, so it is better for all those involved to find out and learn as much as possible about what happens during puberty and adolescence.

These challenges are tackled in the following module.

- Understanding my child

- Supporting my child

- Letting my child go

- External support

2. Understanding my child

This chapter informs you about:

Puberty and adolescence in general

Peculiarities of children with ID during puberty and adolescence

Similarities and differences that help you to understand this behaviour

2.1. Understanding puberty

Photo: Pixabay.com

„Is this object my body?!" A question frequently raised by pubescent people, when physical changes take place within their body.

There are changes in proportion and appearance of limbs, arms and legs become longer, primary sexual features develop, and secondary ones become visible. Hair grows where there was no hair before. For parents’ it is relatively easy to recognize physical changes. It gets more difficult when it comes to tackling emotional elements. There is often an open or silent revolt against regulations, discussions about the time of returning home, the choice of clothing style, appearance and so on. This is when teens become bitchy and aggressive, all but the “best friends” are stupid and parents are just embarrassing. These are signs of puberty.

But how are the changes of puberty perceived by young people?

In the first phase of puberty, the adolescent often feels insecure with the change in their physical appearance. They are almost "taken by surprise" by the physical changes and do not really know how to handle it.

There is a spontaneously increased sense of shame. The child suddenly no longer likes to be seen naked in front of the parents. Self-doubt and depressive moods are not uncommon in this phase. However, these can also result in tantrums.

Their behaviour is affected by physical alteration, as well as hormonal change. Because of change in physical appearance disturbed young people react by violent mood swings to even smaller events. As male sex hormone testosterone acts towards increase in aggression, young boys may especially incline towards violent behaviour. The aggression can be directed against anything opposes the youthful urge to unfold, especially against parents and socially prescribed rules and standards. [1]

In addition to the outbursts of rage, there can be excessive joy and in the next moment remorse for the outburst of rage. Other "new" emotions such as rivalry and jealousy are also being discovered. The adolescent may compare and measure themselves against their peers in an effort to be "the best", and, "the most popular".

Youngsters find themselves in a “tensional field” of familiar childhood kind of relationships and new, yet untested opportunities. This and an unknown future trigger a riot of emotions. On the one hand there are “the pain of parting” and grief over the end of childhood, as well as a fear of loss of security, a feeling of insecurity in the "new" body and doubt. This all stands opposite hope and confidence, confidence in their own strength and rage at everything that opposes their set goals.

In this emotional chaos the question of sexual identity also arises. Who am I as a man or a woman? How do I feel in this role? How do I appear to others? Hormonal change creates interest in potential partners.

Within the Sexual Health module these physical aspects have been described in detail, e.g. see Chapter on puberty.

“The concept of developmental tasks” of Prof. Robert Havighurst [2]

postulated for the first time in 1948 is still valid today. [3]

Every human being has in accordance with his stage of life age-related tasks to full fill. So are these in puberty and adolescence:

-

Autonomy: To attain detachment from the parents

-

To find one’s own identity within the gender control

-

To generate one’s own system of morality and values

-

To develop one’s own future perspectives and / or make a career choice

2.2. Understanding adolescence

Photo: Pixabay.com

The term 'adolescence' refers to the mental maturity process after puberty. In this stage the person is confronted by different developmental tasks. We want to answer these three important questions so that you understand adolescence more:

How does the identity develop? (2.2.1)

How does the youngster develop their own future? (2.2.2.)

How to become independent and autonomous? (2.2.3.)

“Adolescence is a stage of life, where juveniles have to deal with physical changes, have to detach themselves from their parents and build new relationships to their peer group, to integrate their sexual needs and to develop new social and first professional identity.” [4]

2.2.1. Development of an independent identity - How does the identity develop?

"When the adolescent process (search for identity) is completed - in adolescence it continues in a more modest form - independent life and gradual, constructive integration into society begins, which is characterized, among other things, by the multifaceted formation of self-chosen relationships”. [5]

The realisation "I am an independent human being" is an important step on the way to adulthood. On the psychological level, your own orientation is no longer based primarily on the values and way of life of your parents, but on people and things outside the family. The idols of childhood give way to the stars and starlets from media; hairstyles and looks are compared extensively to those of friends and classmates. The views of parents are continuously questioned.

At the cultural level, a personal lifestyle develops that often fundamentally differs from that of the parents. It is possible that from one day to the other the pink girl's room gives way to a black cave or music taste changes completely.

See also "identity" in the Sexual health module.

2.2.2. Development of a life perspective and life planning - How do youngsters develop their own future?

Your own life planning and prospects of further life are among the things that often change in the course of childhood. Career wishes vary from engine driver to astronaut. In adolescence, plans must become concrete. The adolescent develops their own intellectual and social competences that enable them to autonomously fulfil school requirements and later professional qualifications. Career choice and family planning are very important to young people in planning their paths even today. [6]

Job and Occupation

Towards the end of school education, the topic of a career choice becomes important. The emphasis is on the material level, a financial and economic independence and thus financial independence from the parents. The focus is on personal abilities and career opportunities among other things. Young people evaluate their own career aspirations. Recommendations by parents and teachers are considered as per their feasibility and social acceptance. [7]

In the final decision both parents and friends only play an orienting function. There is a strong desire for more information and practical experience in the run-up to career decision.

Living

The next step is spatial separation from the parents, the first home of your own. This step often takes place later in life, because of lengthy training periods and the difficulties in finding a job. What's more, young adults today stay much longer in their parents' homes than before. This may have economic reasons because housing is scarce and expensive. It is also possible that the urge for an early move is not present anymore.

Family

Starting your own family is also often delayed in favour of career. [8] They see their own family as a place of social retreat. Even if the starting a family is pushed further back in life today, it is still a desired goal. Until you have your own family, parents usually remain the first point of contact in times of crisis.

Friendship, peer group (clique) and relationship

To belong to other people, being part of a group and to understand yourself as part of society play an important role in developing a self-image and for well-being. In adolescence, relationship with friends become more important. It makes it possible to try different roles and "identities" within a protected framework, the peer group, and it is also an irreplaceable test field for practicing principles of reciprocity, such as negotiating or sharing opinions. As a result, independent values, different from those of parents can emerge - an important developmental task. [9]

Additionally, youngsters receive validations and security from friends’ as well as support in case of conflicts with parents and/or school. Support in the peer group facilitates emotional detachment from parents. Friends help with separation and search for a lifestyle of your own. In conflict situation, the juvenile is usually opposed to their parents. Recognition by their friends and belonging to a group are more important to them. Standards and admiration of the peer-group are more important than the taste of the parents; anyone can understand this, who has ever discussed about trendy dress styles with a teenager. [10]

Another important task on the path to personality is examining your role as a male or female: What is considered gender-typical in your group determines the framework of personal development. [11]

How friends behave in dealing with the opposite sex, what older group members do and what the parents have exemplified are the reference points the model of the young person is oriented to.

In the peer group, all topics that are of interest to the group, including career choice, are discussed. If a young person wishes to engage in some activity that is not gender specific, the group can employ some pressure on you to adhere to the specific role. In cases like this you require stable support from parents and a strong personality to follow your own plans. In a stable relationship, in case of important life issues, parents always remain to be contact persons. [12]

During adolescence, the initial common “black and white” view becomes somewhat moderated. The ability to accept counter-arguments and to form a complex judgment increases with mental maturity. An adolescent who can engage in discussions with others, reflect on contradictory statement, and express their own opinion has made a big step towards their own personality.

Another important task is to learn relationship skills. Important questions during this task are: "How do I get in touch with other people and start a relationship?", "How do I maintain friendships?", "How close do I want the contact to be?", "How do I deal with crashes?" Different degrees of intimacy and friendship are important learning points in this field. [13]

2.2.4. Becoming independent and autonomous - How to become autonomous?

The evolution of independence starts with the first steps of the child; for the little ones it can be a play afternoon with friends without parental supervision or spending your pocket money as you wish. For older ones this extends to overnight stays with their best friend, weekends with their friends and the first holiday alone without guardians; teenagers prepare for their own lives.

An essential developmental task is to tackle school and professional challenges in an increasingly self-reliant manner. The more tasks are successfully mastered, the more self-confidence can develop.

Areas of "mental autonomy development" can be summarized as:

Detachment from the parents

Further development of your own identity

Building your own ethics and values and acting accordingly

Development and stabilisation of behaviour, thinking about and experiencing, as well as dealing with your own age

Developing a future perspective with the aim of becoming materially independent and exercising a profession

Taking on adult social roles, e.g. through employment, choice of a partner, partnership and marriage, as well as parenthood

2.3. Specialities by PWID

Photo: Pixabay.com

For adolescents without disability, a desire for autonomy and independence is usually supported by the parents, and they become gradually equal. Many parents find attempts to gain power, personal responsibility and self-determination by a child with ID stressful, especially when it is accompanied by difficult behavioural patterns.

Many parents find it difficult to accept the child as an adult, because their linguistic and cognitive skills do not exceed a child's proficiency level. This makes it harder to develop more autonomy. The danger is a fixation on the level of "eternal childhood". [14] The fact that many PWID is not trusted to live an independent life is also often due to the fact that they could not sufficiently initiate and try it out. Because of cognitive limitations, the self-assessment of the adolescent is often less trusted: sometimes boundaries are vigorously enforced. The danger that the adolescents are being tightly controlled is very high. [15]This chapter gives you an overview of specifics of how a person with ID (PWID) grows up. We believe the following points are especially important:

Development stages are non-contemporaneous (2.3.1.)

Cognition is missing as a resource (2.3.2.)

Replacement symptoms are not always recognizable as such (2.3.3.)

Physical maturation as a development opportunity (2.3.4.)

The peer group as a social resource (2.3.5.)

The drive for replacement is fragile - the importance of special dependency (2.3.6.)

2.3.1. Development stages are non-contemporaneous

Photo: IB Sued-West gGmbH

Like everyone else, PWID undergo the physical aspects of puberty. This is basically the same as with others, but maybe its timing is different. In these cases, puberty sometimes starts up to 5 years later and often lasts longer. Mental and emotional development drifts apart.

The psychological structure of PWID does not deviate from non-disabled people in principle. Thus, every maturation feature of an average person can also be observed under certain conditions or at certain times during the development of a PWID. [16]

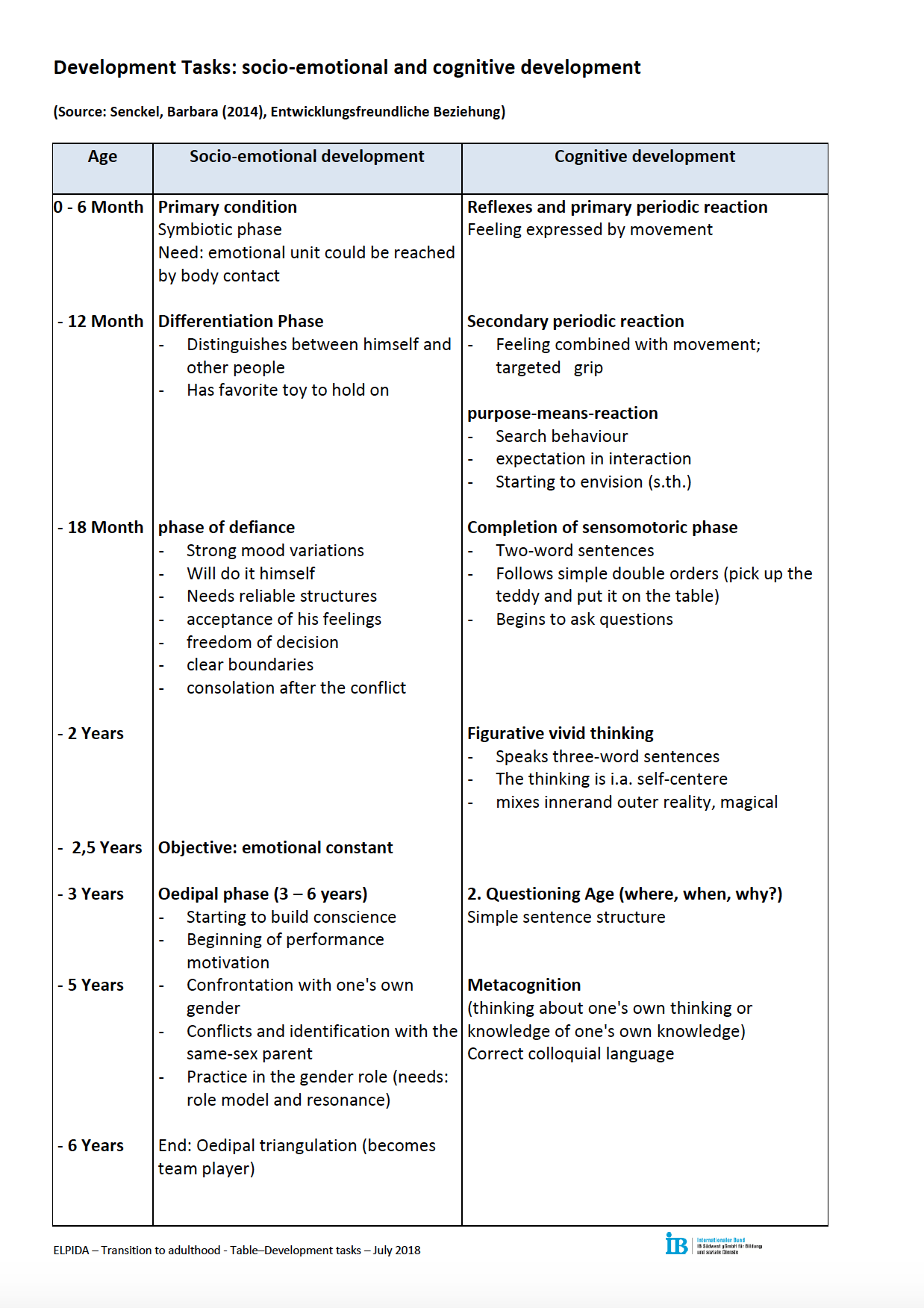

It is key not to consider cognitive advancement on the whole as a measure of overall development. "The need to detach from the parents during adolescence and to achieve a degree of self-reliance as a child is a maturing task, which is largely independent from intellectual advancement." [17]Child development scoring matrix measures two developmental areas - the socio-emotional and the cognitive:

Parents and carers can check the development level of the PWID by trying to use the table to determine first cognitive, then emotional age. The person should be encountered at the respective stage of development and the different development areas should be strengthened separately, so that the person can reach the next stage of development. [18]

2.3.2. Cognition as a resource is missing

Abstract thinking helps to process experiences and arrange them for yourself.

A primary school aged child can e.g. think logically about reasonable problems and review the experience. But it always relates to what they see or experience in the here and now. It is only during adolescence, that the ability to think abstractly is fully developed. The child can now derive logical consequences based on theoretical principles.

For PWID the ability of abstract thinking, depending on the degree of disability, is less pronounced. The opportunity to reflect on the change taking place is often not given.

The hormonal side effects of puberty such as mood swings, sudden outbursts of anger or new reactions of the milieu to expressions of your own will often cannot be well-managed by intellectually disabled people. They often feel helpless experiencing them. [19]

Adolescents also perceive limits clearer, that are often associated with painful processes. E.g. a PWID attending an integrated school: growing cognitive discrepancies become more apparent and adolescents of the same age withdraw. Being different is experienced painfully by the adolescent. They feel increasingly marginalized and increased rivalry can be even more problematic.

Another example is an adolescent who grew up in an institution. They are more likely to suffer from the limits set in this environment and want to live free as "normal" youth. However, everyday life is often relatively structured and designed for living together in a larger group. The individual desire to dissociate and expand can often be less realized in this context.

Whatever boundaries teens may struggle with, it can lead to emotional frustration and injury. These are then often reacted on with aggressive, regressive or depressive behaviour. [20]

Photo: pixabay.com

2.3.3. Detachment symptoms may not be recognized as such

"The obvious and covert detachment and impulses of being self-sufficient by adolescent or already adult daughters and sons are often classified by parents as disability-specific problems and are neither understood, nor supported as necessary maturing steps on the way to be a grown up.Detachment handicap is a factor that get far too little attention.” [21]

It is important for adolescents with ID, that caregivers take their changed behaviour seriously and as a positive sign of development. That is not always easy. Thus, e.g. rule violations or denials are understood as a "simple" discipline problem, even though the young person is trying to gain new freedom for themselves. Especially when linguistic development make debate limited, it is difficult for both, parents and children to understand what is going on.

However, when it comes to the issue of replacement and a caregiver does react, the teenager becomes more helpless than before. Sometimes they only have anger or resignation and withdrawal. If they are not understood in their attempts to detach themselves, youngsters will not receive support for cutting the virtual umbilical cord.

What this means and how you can detect detachment symptoms as such is described in Chapter 3.1.1.

2.3.4. Physical maturation as a developmental opportunity

"Even severely disabled people who do not exceed the mental development level of a three-month-old infant show emotional hormonal side effects of puberty. ... Even a spiritual awakening can be observed with the severely disabled ... Thus, even for a mentally disabled person puberty is a time of upheaval that influences the overall personality and opens up new opportunities for development. However, which development steps can actually be carried out depends on the type and degree of disability." [22]

Dr. Senckel emphasizes that physical development can be an engine for social development, even with persons having complex disabilities. It is important to perceive and support this. She reports on a severely disabled man, who refused to be touched until his mid-20’s. He changed this behaviour at the beginning of his puberty. He made contact with other people, even timidly reaching for his caretakers. Nobody trusted him to do this earlier on.

Physical changes unsettle some PWID so much that they largely ignore them. For example, some girls wear extra-large sweaters when the breasts start to expand in order to conceal them.

Time of change also in neurobiological area:

A reconstruction of brain tissue takes place among other neurological phenomena during adolescence. Thus, with the onset of puberty, many nerve connections within the brain that are no longer used are dismantled. Grey substance, that forms the nerves of the cerebral cortex, reduces measurably and white matter that is responsible for the rapid exchange of information, increases. The juvenile brain increases its computing power up to 3000 times. Adolescents forget unused or unsolicited matters and become more responsive in their attention and decisions. [23]

2.3.5. The peer group as a social resource

Photo: IB Sued-West gGmbH

The peer group is also an important resource for the development of puberty and adolescence for intellectually disabled adolescents.

"Within the peer group disabled young people are establishing their status; there is a strength measurement against rivals: aggressive confrontation and submissive serfdom are not unusual. But it can also develop sustainable friendships, so that new forms of social behaviour can be learned. Of course, with the sex drive also the interest in the opposite sex awakens. Here, too, the longings are like those of the non-disabled. A successful friendship makes an important contribution to the development of identity; not replaceable by adults." [24]

However, this resource is more difficult for them to access. These young people are usually limited in their mobility and independence. They find it harder to build and maintain relationships with the peer group outside of the family and school. In addition, contacts usually take place under supervision and are usually regulated by reference persons. It is also harder for them to engage in and use social infrastructures in their local environment. For example, they are not welcome at local youth club.

A particular difficulty for adolescents with disabilities is that they are often dependent on their parents or other caregivers for encounters with the peer group. They are less exposed to risks, but also have a limited field for practice. They live with a contradiction: meetings with the peer group as a support to the detachment from the parents must be accepted and accompanied by the parents. [25]

More about the meaning of the peer group and how you can support your child in Chapter 3.1.2.

2.3.6. The drive to detachment is fragile - the importance of special dependence

"What would happen to a person without detaching from the family? How many of them does still live with mother and father, are dependent on them and limited to the immediate living environment of the family? Who is their ideal if they live such a life?” [26]

Adolescents with disabilities want to get rid of dependency from the parents. This means they have an urge to go outside and friends become more important. At the same time, they depend on family support in many aspects. They need support in everyday life, bodily care, maintaining social contacts and much more.

"As far as attitude towards your own wishes and abilities is concerned, many adolescents with disabilities have ambivalence: on the one hand they want more independence, self-determination and autonomy; they also want to live "like others"; but the more they become aware of the fact that they depend on the support their parents offer them, the more they feel they are losing this safety." [27]

The care of the parents was and still is vital.

This ambivalence pulls them back into the family circle. Young people with mental disabilities are even more affected be this tension than others. The drive for detachment is thus very vulnerable.

Parents are aware of their child’s dependencies and these do not resolve by themselves because a pubescent teenager no longer wants his parents. [28] In this respect, the child with intellectual disabilities is also dependent on the parents in the matter of separation: the parents themselves must deal with detachment and also develop new future perspectives for themselves.

This raises the question of who should provide the necessary support for the child in the future. Parents are often the ones who (must) decide on measures and speed of steps here.

What helps parents to "let go" is described in Chapter 4.

Another difficulty for the parent-child relationship in adolescence is the role of the parents in supporting the child in the best possible way. This task is socially mediated. This is brought to parents from the beginning onwards and is ambivalent for them. The parents should accept their child as it is. At the same time, they should make sure that the youngster changes and becomes as normal as possible.

This means further pressure on those responsible. A child should function as inconspicuously as possible in society. For example, it is embarrassing for everyone, when a child suddenly shouts in public. In case of a small child, this behaviour is still accepted, but not in case of a disabled juvenile. How much (unobserved) experimentation can be tolerated in public? "Negative reactions of e.g. relatives or the public can intensify the bond of a family, so that a great intimacy in the familial relationship arises (..) and the child is additionally held in his dependent and autonomous role as a disabled person. [29]

“What is acceptable and in what situation?” This is not easy, because adolescents need challenges that are always associated with risks. However, because of their limitations, young people are often less able to protect themselves from injuries. Overstraining threatens to setback the development. This can go so far that the world out there seems too dangerous to these youngsters and this binds them even closer to the parents. However, borderline experiences are also important. If the developmental task of detachment is permanently postponed to later, it will get harder. The external incentives then must become even stronger. [30]

In this process young people have to experience many of their own fears as they are usually very much aware of the fears of their environment, especially of their parents. Such fears are often inaccessible, but still noticeable. This makes young people even more worried, especially when they fear losing their parental support. Therefore, if the desire for your own life threatens the relationship with the parents too much, it must be warded off. The easiest solution for this is also a closer bond with the parents; the dependency is reinforced. [31]

It could be helpful to talk to your child about your fears as well as theirs, and to encourage them to discover the world "on their own".

Please find additional information in the Communication module.

Further information on support can be found in chapters 3.1. and 3.3.

ACTIVITY: "Mobility Training"

Together with your child, create directions to a specific location. Read this for guidance: Mobility training

Photo: Pixabay.com

2.4. References

1 Senckel Barbara (2015), Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München. S. 211

2 Havighurst, Robert J (1949): Adolescent Character and Personality, Chicago

3 Hurrelmann, Klaus; Bauer, Ullrich: Einführung in die Sozialisationstheorie, Beltz, 2015

4 Streeck-Fischer, Annette (2004): Adoleszenz – Bindung – Destruktivität, Bucheinband, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart)

5 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München. S. 180

6 Albert, Mathias; Hurrelmann, Klaus; Quenzel, Gudrun: Jugend 2015: 17. Shell Jugendstudie. Shell Deutschland (Hg)

7 Albert, Mathias; Hurrelmann, Klaus; Quenzel, Gudrun: Jugend 2015: 17. Shell Jugendstudie. Shell Deutschland (Hg)

8 Papastefanou, Christiane (2000): Der Auszug aus dem Elternhaus. Ein vernachlässigter Gegenstand der Entwicklungspsychologie - In: ZSE : Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation 20,S. 55-69

9 Fend, H. 2005. Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters Taschenbuch. WS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. 3. Aufl. Wiesbaden. S. 309

10 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München. S.93

11 Wetzstein, T.A.; Erbeldinger, P.I.; Hilgers, J.; Eckert, R. (2005): Jugendliche Cliquen. Zur Bedeutung der Cliquen und ihrer Herkunfts- und Freizeitwelten. Springer. S. 20f

12 Budde, J.;Debus, K.; Krüger,S.(2011): Ich denk nicht, dass meine Jungs einen typischen Frauenberuf ergreifen würden. Intersektionale Perspektiven auf Fremd- und Selbstrepräsentationen von Jungen in der Jungenarbeit. In: Gender: Zeitschrift für Geschlecht, Kultur, Gesellschaft; Jg. 3, S. 119-127.

13 Fend, H. 2005. Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters Taschenbuch. WS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. 3. Aufl. Wiesbaden. S. 309

14 Klauss, T./ Wertz-Schönhagen, P. (1993): Behinderte Menschen in Familie und Heim – Grundlagen der Verständigung und Möglichkeiten der Kooperation zwischen Eltern und Betreuern. Weinheim

15 Ekert, B.; Ekert, C. (2010): Psychologie für Pflegeberufe. Thieme, Stuttgart

16 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München. S.97

17 Lempp, R.: Lebensphasen – Lebensorte. Schwierigkeiten des Erwachsenwerdens für geistig behinderte Menschen. In: Wacker, E./ Metzler, H. (Hrsg.): Familie oder Heim. Unzulängliche Alternativen für das Leben behinderter Menschen? Frankfurt/Main 1989, S.152-168

18 Senckel, Barbara (2014), Entwicklungsfreundliche Beziehung

19 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München. S.98

20 Langner, Anke 2009: Behindert werden in der Identitätsarbeit. Jugendliche mit geistiger Behinderung – Fallrekonstruktionen. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag

21 Hennies, I.; Kuhn E. J. (2004): Ablösung von den Eltern. In: Wüllenweber, Ernst (Hg.): Soziale Probleme von Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung. Fremdbestimmung, Benachteiligung, Ausgrenzung und soziale Abwertung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. S.135

22 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München. S.97f

23 Giedd, Jay (2002), Psychiater: Interview https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/teenbrain/interviews/giedd.html

24 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München. S.100

25 Uphoff, G; Kauz, O; Schellong, Y (2010): Junge Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung am Übergang zum Erwachsenwerden – Bildungsprozesse und pädagogosche Bemühungen. In: Zeitschrift für Inklusion, Ausgabe 01/2010

26 Klauss, T. (2015): Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung – Ablösung vom Elternhaus (Winnenden 13 11 2015 S.15)

27 Klauss, T. (2015): Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung – Ablösung vom Elternhaus (Winnenden 13 11 2015. S.15)

28 Hennies, I.; Kuhn E. J. (2004): Ablösung von den Eltern. In: Wüllenweber, Ernst (Hg.): Soziale Probleme von Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung. Fremdbestimmung, Benachteiligung, Ausgrenzung und soziale Abwertung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

29 Thiersch, H. : Lebensweltorientierte Soziale Arbeit, 1992, 9. Auflage, Weinheim 2014

30 Havighurst, Robert J (1949): Adolescent Character and Personality, Chicago

31 Hennies, I.; Kuhn E. J. (2004): Ablösung von den Eltern. In: Wüllenweber, Ernst (Hg.): Soziale Probleme von Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung. Fremdbestimmung, Benachteiligung, Ausgrenzung und soziale Abwertung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer

3. Supporting my child

Photo: IB Sued-West gGmbH

"As long as the child is still small, there is often a dense network that offers help: Counselling centres, parent groups, early intervention centres and much more. But when the child gets older, the parents often feel left alone. [...] Parent groups are separating again, because the disabilities of children and their developments are so different that the interests of the families are drifting apart. Brothers and sisters go through puberty and confront with the handicapped child, which is difficult for parents to bear. The PWID also changes. It goes through puberty and may show behavioural peculiarities, because they want to live more a self-determined life. But a child with a disability lives more dependent on his or her parents than other children: How can a person get rid of the umbilical cord in this addiction?” [1]

How can I support my child on their way to adulthood, so that they can live a self-determined and happy life despite their special needs? What can I pass on to him or her? How can I foster their personality development, life planning and independence?

This chapter is about how you can support your child in the following developmental tasks:

On the road to identity (3.1.)

During life planning (3.2.)

Concerning independence (3.3.)

3.1. On the Road to Identity

This Chapter will give you suggestions and ideas on how to help your child find their own identity. The following points which will be especially considered:

Noticing behavioural differences as detachment symptoms (3.1.1.)

Being part of a peer group (3.1.2.)

Let them experiment (3.1.3.)

3.1.1. Noticing of behavior differences as part of detachment symptoms

As a reminder: First of all, parents must realize, that their child is beginning to take over, which is not always so easy for PWIDs, as they often develop in a diverging way, see also Chapter 2.3.1.

A pubescent with ID may not have reached the same level of development in all areas of personality:

"So, the caregiver often faces an adolescent, who strives for his detachment, fights for his freedom and behaves like a tyrant, but in the next moment expresses symbiotic needs, seeks bodily contact, cuddles and suffers from severe separation anxiety. It is important to take all levels of development seriously, each at the moment when it determines behaviour. This requires the ability to constantly change the contact level: If the symbiotic wishes prevail, they should be considered, if the young person rises to a higher level of development, he should be met there. This is the best way for him to develop his personality as a whole." [2]

It can be helpful in this context to focus your attention on significant physical changes in the child.

The changes in the process of growing up start at the physical level, signs of which are, for example, first menstruation or a voice rupture. These "signs" are points of reference and orientation, that indicate a new phase of development and entail necessary changes in the parent-child relationship.

How you can support them at this stage:

Make your child aware of the change and help them to classify it

Use these signs and landmarks as an occasion for a ritual or gift. For example, buy a gift that represents the new stage of life or issue a certificate for growing up and thereby make the change clear

Show your child how proud you are of their development

Physical changes are followed by changes in behaviour.

As described in chapter 2.3.3., they appear in various ways and are often difficult to recognise as symptoms of detachment. [3] One expert rightly notes that people with a mental disability often receive little feedback on their social behaviour. Regulatory actions are taken or peculiarities are tolerated. This allows them to develop little self-regulation as they face little demand. There are therefore no disputes in which the young people have a chance to make a difference themselves.

How you can support them at this stage:

In case of doubt, take up conflicts as conflicts about detachment, independence and talk to your child about it

Give new freedom to the will of the young person in conflicts. Let it be enforced for once - even with possible negative consequences.

Accept and support the desire for privacy - e.g. a closed room door.

Do not use your child's level of cognitive development as a measure of detachment.

Be aware of your child's lack of intellectual resources to process these things (processes). Support it by talking to him about these things and giving him emotional support.

The art is to give free space as parents or educators without withdrawing emotionally.

3.1.2. Being a part of a peer group, have intimate relationships.

As described in chapters 2.2. and 2.3.4., relationships and experiences with the peer group are important resources / factors for personality development in adolescence. It is associated with special hurdles for PWIDs.

How you can support them at this stage:

Support contact with peer groups (peers), even outside school and the workplace.

Let your child plan activities with friends and support them in executing these plans - even if they do not meet your expectations.

Accept the behaviour in the group, even if you do not like it.

Do not over-value changing friendships and enmities.

Try to organise necessary company by other people in connection with the peer group.

Educate your child. Enable peer experience in unguarded, protected rooms. Allow e.g. the young people to withdraw to their room.

Sexual development is a particularly sensitive issue and a dilemma for many parents, as they want to enable their child to have experiences, but also want to protect them from abuse. However, sexual experiences in the peer group are important for the sexual development of children. Only forward-looking steps will help here.

Experts guess: Education and experience in relationships with peers protect against abuse. [4]

For further information, please refer to the Sexual Health module. e.g. see Chapter "Right to know your own body".

3.1.3. Being able to experiment

Foto: Pixabay.com

- "Why

is experimenting important?"

Playful experimentation initiates learning processes and activates social skills. Decisions must be made in concrete situations. "How should I behave?" Responsibility must be taken for decisions. These processes challenge and promote the different parts of the personality.

At the same time, experimentation is associated with risks and caregivers face the question of what risks they expect for themselves and their children.

An expert goes so far as to saying: "Young adults with intellectual disabilities need to be consciously exposed to normal life risks, as these impose significant developmental impulses on identity and personality development."

However, risk often puts parents in a dilemma as dangers are quite real.

Nevertheless: "Experiences help to get a realistic view of yourself. This view helps to accept if you are not able to do something, which in turn is the prerequisite for any learning - otherwise, every non-ability is an offense!" [5]

How you can support them at this stage:

Enter into conflicts and offer a stable emotional basis. [6]

Conflicts have a developmental function as they are an element of negotiation processes between parents and young adults. [7]

Conflicts offer possibilities to gain distance, there is a confrontation with different points of view and arguments. [8]

A fight for rules can be a separation conflict. Parents have more "power" e. g. to insist on rules. It would be important that their rebellion is sometimes successful. [9]

Let your child take risks, e.g. smoking, going to the disco, travelling on their own, dealing with pocket money or going out with a friend with whom they can feel separated. [10]

-

"Why are unobserved rooms so important?"

The experience of people with intellectual disabilities is also limited by the fact that they are much more often under supervision in general. There are hardly any unobserved rooms.

"Little is possible without the consent of the parents."[11]

In the area of individual friendships and love relationships, it is also often the parents who (together with other parents) make appointments and organize driving services.

If the young person is allowed to have activities and experiences without parents, it can be assumed that a separation from parents will be more successful and positive.

It means that children who are granted situations without direct control they can experience their strengths and weaknesses independently in tend to develop a sense of identity and autonomy. [12]

"Why are external supporters important?"

Professional supporters have the opportunity to give young people an autonomous experience, e.g. to meet friends without parents, to go to the cinema or simply to exchange ideas. At the same time, parents and families are relieved by the thought of company. [13]

If escort is necessary: there is a difference between the mother or father accompanying couple in love on a visit to the cinema of a or for example an employee of a leisure program doing so. It also makes a difference, when a group of young people with professional company go to a disco at the usual times (after 23:00).

You can learn more about external supporters from Chapter 4.

3.2. During Life Planning

Photo: pixabay.com

Video: "What is important in life to me"

Questions of life planning do not always come at a time when parents and young people welcome it. On the one hand, important decisions must be made on possible training, professional development and forms of living. On the other hand, young people are already busy with changes anyway. They are confronted, for example, with a number of interrupted relationships such as finishing school or switch to adult health care. Other changes in the living environment can also reduce the willingness to make plans for the future. To get closer to the wishes of your child "the method of personal future planning (PZP)" could help, also for small targets, see chapter 5.1.

This chapter is about the life planning during transition to adulthood. We especially intend to talk about work and education, living and health, and therapy:

-

Work / Education

Professionally and educationally, how much choice do PWID really have?

Depending on the severity or type of impairment, the curriculum vitae often appears pre-defined and institutionalized. In some cases, disability-specific offers are increasing, e.g. for people with an autism spectrum disorder. However, if the young person wishes to work in the first labour market (which is an objective of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities), this requires a lot of perseverance and energy from the parents in implementing an extraordinary individual solution.

See further information in Chapter 5 and the Human Rights module, especially in Chapter 4 "Employment for PWID".

This checklist may also help you to keep track: Checklist for vocational preparation.

-

Living

The time to move out is currently - similar to young adults without mental disabilities - perceived as favourable when changing into working or studying, as changing situations can be combined well with moving out.[14]

The ideal case would be, of course, to wait until the child develops their own impulses for leaving. This often does not seem to be possible, and parents must take active steps.

At the same time, one should be aware that professional arrangements cannot offer "equal" proximity and care. It is acceptable as long as it corresponds to what every young adult experiences and has to learn: to get along in different "worlds" and "frameworks".

However, in order to avoid crises, it is also important, that extraction is not too early so as not to overstretch them, so that young people themselves also want it.

"Desire" to move out, on both sides - how can you make them wake up? It's a tightrope walk: entice, push - with as little pressure as possible! [15]

Sometimes children have to move out much sooner due to the distance from their training or work or due to special needs or if there are constraints, e.g. Waiting lists of dormitories. If extraction is "prescribed", however, the child can not perceive it as a self-determined step of detachment. They are thrown out of the nest. This is also very difficult emotionally for parents. "Being active in relocating a child must trigger ambivalent feelings and requires a redefinition of one's role and responsibility."[16]

-

Health / Therapy

People with intellectual and/or multiple disabilities often have additional chronic diseases or even disposition to acute diseases. They have special needs in terms of the scope and quality of their health care.

This is particularly serious with the transition from paediatric and adolescent health care to an adult one. Parents are sometimes shocked by unfamiliar atmosphere and other ways of working.

Some children lose contact with specialised health care when they stop using paediatric services. Effective treatment standards have been established for some paediatric and adolescent medical conditions, but no comparable care structures exist in the adult medical field.

One reason for this is, that life expectancy has increased for people with some complex and rare diseases due to improved medical standards. Adult health care has yet to catch up with this fact.[17]

In some countries (Germany, England) medical centres for adults with disabilities are there to ensure continued care of socio-paediatric patients in adulthood and thus facilitate transition.

Parents often have expert status for special illnesses of their child.

"Since these patients are not expected to become truly independent when they enter adulthood, parents retain their position as responsible persons and must again find reliable contacts in adult health care with sufficient understanding, time and professional expertise to take over the complex care of these patients and to respect the expert role of parents.“

Becoming self-employed or supported by others - parents are important partners that actively participate in the process of life planning and accompanying the young adult.

To advise young people in their life planning and to develop goals, you can arrange "Personal Future Planning".

You can find out which professional services can support you and your child in Chapter 5.

3.3. Concerning Independence

Photo: Pixabay.com

In this chapter you will find suggestions on how you can support your child in the process of becoming independent. The following areas will be discussed in more detail:

Promoting strength (3.3.1.)

Finding new learning fields (3.3.2.)

Using the trust of external people in the child (3.3.3)

ACTIVITY: “Create activity cards”

a.) Consider a household activity that your child learns or takes over.

b.) Create an "Activity Card" with your child.

An example for an activity-card: Cleaning a bathroom

3.3.1. Promoting strength

Young people need a strong self-esteem.

"Good looks, sports activities and friends usually contribute to a good self-esteem. Young PWID must know their strengths and at the same time cope with their weaknesses, for example with an appearance that may not correspond to the conventional ideal of beauty." "Ultimately, they have to be able to do more than other to be accepted to be different and still liked." [18]

Photo: IB Sued-West gGmbH

To develop strengths, children with severe disabilities need support. It is important to respond to the individual situation of the child and to find a balance between support and demands. Special support approaches have been developed for special forms of disability, e.g. the TEACCH concept for children with autistic disorders.

The trend in psychology and education – focusing on strengths rather than shortcomings - comes in various forms and approaches, such as salutogenesis and resilience concept, and has led to a resource-oriented attitude.

Resources are factors that can strengthen people in a situation.

"They can be created both in the persons themselves (personal resources) and also be brought to the person by the environment (environmental resources). If resources are pronounced, they support human development also by compensating for deficits and developmental disorders". [19]

Everyone has strengths.

For some they are intensive, for others less so. In some cases, the soft factors are "slumbering" and are still undiscovered. When people are asked about their strengths, they often do not have a clear and convincing answer and they have to first think long and hard.

So how do you intend to use your strengths, if you are not aware of them? By going on a search (be a treasure hunter!):

Make it your task to identify and use the strengths and abilities of the children. Helpful questions are: What is your child really good at? What is very easy for them? Do they have any special skills?

Include your family, friends and acquaintances because their opinion is from the "outside" and of great importance that opens new perspectives!

It is crucial that you become aware of your strengths from time to time, develop them and, above all, actively use them. As with any training, the practice makes you a "master".

Be creative and visualize strengths, e.g. through a collage, or collect the strengths and resources in a treasure chest that can be retrieved when necessary.

Compare your child less with other children in their development but rather look at their uniqueness. The best way to keep track of developments is to regularly draw up small advancement plans and reports.

Every human being has resources that are more or less activated and are available for coping with life situations. [20]

Encourage talent because our expectations for success are influenced by how much we believe in our strengths. [21]

Look for role models and exemplary people for managing disability in adulthood. - Role models, idols, quotes can steer your actions in the desired direction. Imitation is one of the three major ways of learning. "Models show you that what you still consider impossible in your mind has long been a reality in somebody’s life."

For the adolescent it can create a very frustrating situation, if they lack chances to practice independence. [22]

How you can support your child with it:

Be aware that encouraging your child to become more autonomous does not mean abandoning or desert the child. [23]

How can young people (on a small scale) gain experience of being able to stand on their own two feet - even with the support of other people - but in such a way that they themselves are "in the centre"? Create incentives for it! [24]

3.3.2 Finding new learning fields

"In fact, the parents of PWID are suddenly confronted with desires, for example the acquisition of a driving license, which are not necessarily realizable. I emphasize "not necessarily", because there is no rule about it: I have often been impressed by young PWID by their abilities. Even if the chances of success are low, it is not good to spare your child a disappointment at all costs by preventing it from trying out. I refer to the example driver's license: I know parents who let their child take an hour of driving. It ended in failure, but at least they gave their child the chance to try. "[25]

Learning takes place unconsciously in many everyday life situations. Experiential knowledge, experimenting, trying out, absorbing and applying information - behind all these activities there is a learning process. Learning means sharing, creating, discussing and linking information. Learning means to become active. It requires curiosity and motivation from the individual.

The aim of all learning is to improve the quality of life by increasing the ability to act in a social, professional and private context. Learning is a lifelong, living process, that leads to a reflected relationship with oneself, with others and the world. [26]

How you can support your child with it:

Do not offer automatically "all-round care" any longer. Your children need resistance. They can't automatically get everything. To learn how to take responsibility, it is important, that your children learn something for themselves. [27]

Do you have any ideas on how you can incorporate gaps in their daily routine? Examples: Have them prepare their own lunch, fold together their own clothes, get up without wake-up service. Even if the carrot is not perfectly cut, practice makes you perfect.

More independence or a sense of achievement can be incentives for the completion of tasks. Children who have had to solve a number of problems themselves have proven to be happier. [28]

In order to create a sense of achievement, it is important to set challenges and assign tasks that are initially easy to complete and can be divided into very small steps.

These tasks make it clear what your child can and cannot do, what their development possibilities and limits are - including those related to disability.

Photo: IB Sued-West gGmbH

"Take advantage of educational opportunities!"

Educational opportunities help you to adapt to the demands of life.

With regards to people with disabilities, adult education has the task of facilitating new experiences and processing existing ones, [29] imparting knowledge and providing support for self-determination and shaping their life. [30] Information is important for making decisions.

PWID in particular often have problems making decisions as they had rarely been given options in the past. A largely self-determined life, however, means that decisions with more or less far-reaching consequences have to be made from time to time, e.g. the decisions for a job. [31]

How you can support your child with it:

Parents should encourage young people to discover and pursue their own interests or to actively respond to changes in everyday life.

Enable participation in educational opportunities.

3.3.3. Use the trust of external persons in the child

External support in adolescence has many aspects:

It helps young people to make experiences independent from their parents, e.g. in a peer group (chapter 2.3.5.), but it also helps you as parents to "let go" and develop a new relationship with your child.

Your child's self-confidence is strengthened through overcoming obstacles, courage and confidence. The more often your child is given the opportunity to try out (experiential spaces) and master things, the better they learn to deal with frustration and self-confidence will increase.

Parents repeatedly experience that things practiced for a long time will only start working with an external person. [32]

The confidence of external persons has the advantage that routines are interrupted. Even small changes in the process can require a rethinking and new behaviour. A "different" examination of the person and his strengths and weaknesses takes place, detached from the character of attachment and dependence.

How can you support your child here:

Are there tasks and roles that can be transferred to other family members and persons?

It is important that these other supporters help experimentation. This creates new development spaces.

Have you ever wandered which areas of your support tasks can be outsourced to external supporters or offers?

3.4. References

1 Beyer, I. (2013): Unser Kind wird erwachsen. Das Eltern-Magazin der Bundesvereinigung Lebenshilfe. 1. Auflage 2013. Hrsg. Lebenshilfe e.v., Marburg. S.7

2 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München.

3 Fischer, U. (2006): Bindung und Ablösung bei schwer geistiger Behinderung. In: Bundesvereinigung Lebenshilfe (hrsg.). Schwere Behinderung – eine Aufgabe für die Gesellschaft! Marburg,S. 273 – 283

4 Achilles, Ilse 2010: „Was macht Ihr Sohn denn da?“ Geistige Behinderung und Sexualität. Ernst Reinhaldt Verlag, München, Basel. 5. Überarbeitete Auflage.

5 Uphoff, Gerlinde (2018): Interview im Rahmen des Projekts ELPIDA am 20.02.2018

6 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München.

7 Fend, H. 2005. Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters Taschenbuch. WS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. 3. Aufl. Wiesbaden. S.78

8 Dreher & Dreher 2002 in Schultz, A. (2010): Ablösung vom Elternhaus. Bundsvereinigung Lebenshilfe (Hrsg.)

9 Uphoff, Gerlinde (2018): Interview im Rahmen des Projekts ELPIDA am 20.02.2018

10 Agthe-Diserns, C. / Mercier, M. 2001: Erwachsen werden und Behinderung – Brüche und Bezüge. http://insieme.ch/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/d_542_Erwachsen_werden.pdf / 12.02.2018

11 Uphoff, G; Kauz, O; Schellong, Y (2010): Junge Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung am Übergang zum Erwachsenwerden – Bildungsprozesse und pädagogosche Bemühungen. In: Zeitschrift für Inklusion, Ausgabe 01/2010

12 Ekert, B.; Ekert, C. (2010): Psychologie für Pflegeberufe. Thieme, Stuttgart. S.74

13 Eckert, A. (2007-2) Familien mit einem behinderten Kind. Zum aktuellen Stand der wissenschaftlichen Diskussion. Quelle, In: Behinderte Menschen, (Nr. 1 / 2007) 1, S. 40 – 53

14 Fehlhaber, C. (1987): Ablösungskrisen bei geistig behinderten Jugendlichen. In. Lempp, R. (Hrsg.): Reifung und Ablösung. Bern, Stuttgart, Toronto, S. 157-160

15 Uphoff, Gerlinde; Kauz, Olga; Schellong, Yvonne (2010): Junge Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung am Übergang zum Erwachsenwerden - Bildungsprozesse und pädagogische Bemühungen. In: Zeitschrift für Inklusion, Ausgabe 01/2010 online unter: http://bidok.uibk.ac.at/library/inkl-01-10-uphoff-bildung.html zuletzt geprüft 21.05.2018

16 Klauss, T. (2015): Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung – Ablösung vom Elternhaus (Winnenden 13 11 2015 S.10)

17 Wikipedia" Transition (Medizin) --- Wikipedia Die freie Enzyklopädie ,2018 "https://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Transition_(Medizin)&oldid=173730848", Zugriff am 23. April 2018

18Retzlaff: Familien-Stärken: Behinderung, Resilienz und systemische Therapie. Stuttgart, Klett-Cotta, 2010. S.244

19 Kiso, C. / Lotze, M. / Behrensen, B.(2014): Ressourcenorientierung in KiTa & Grundschule. nifbe-Themenheft Nr. 24, Im Eigenverlag

20 Kiso, C. / Lotze, M. / Behrensen, B.(2014): Ressourcenorientierung in KiTa & Grundschule. nifbe-Themenheft Nr. 24, Im Eigenverlag

21 Friedrich, S. (2010). Entwicklung einer ressourcenorientierten Haltung. In T. Möbius & S. Friedrich (Eds.), Ressourcenorientiert arbeiten. Anleitung zu einem gelingenden Praxistransfer im Sozialbereich (pp. 39-‒50). Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

22 Schatz 1998, 135 in Schultz, A. (2010): Ablösung vom Elternhaus. Bundsvereinigung Lebenshilfe (Hrsg.).

23 Agthe-Diserns, C. / Mercier, M. 2001: Erwachsen werden und Behinderung – Brüche und Bezüge.http://insieme.ch/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/d_542_Erwachsen_werden.pdf / 12.02.2018

24 Uphoff, Gerlinde (2018): Interview im Rahmen des Projekts ELPIDA am 20.02.2018

25 Denis Vaginay, Arzt und Dozent für Klinische Psychologie http://insieme.ch

26 https://oebib.wordpress.com/2010/11/03/lernort-bibliothek-%E2%80%93-zwischen-wunsch-und-wirklichkeit-teil-3/ Zugriff am 05.05.2018

27 www.praxis –jugendarbeit.de Zugriff am 28.04.2018

28 www.praxis –jugendarbeit.de Zugriff am 28.04.2018

29 Uphoff, G; Kauz, O; Schellong, Y (2010): Junge Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung am Übergang zum Erwachsenwerden – Bildungsprozesse und pädagogosche Bemühungen. In: Zeitschrift für Inklusion, Ausgabe 01/2010

30 Fornefeld, B. (2000): Einführung in die Geistigbehindertenpädagogik. München, Basel. S.119

31 Döbling, K.(2004): Förderung von Selbstbestimmung und Integration von Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung, München, Disserta Verlag, Hamburg

32 Uphoff, Gerlinde (2018): Interview im Rahmen des Projekts ELPIDA am 20.02.2018

4. Letting go - What does detachment mean for parents?

This chapter want supports you to in

- dealing with upcoming changes in the family system.

- gaining knowledge in order to modify (actively) your role as parents.

- thinking about which support services and responsibilities can be handed over.

- reflecting on the advantages and disadvantages of „parents as legal guardians“.

- seeing the significance of the meetings with other parents and the possibility for exchange among each other.

It is important to know that detachment does not mean to break up the bond with your own children. The child will always have a relationship to the parents. The more stable the relationship is within the family, the stronger it will be, when the child becomes independent.[1] The bond is not cut, it is modified and reconstructed.

"Detachment comprises all developments within the parent-child-relation." [2]

Many parents put an equation mark between moving out of the parental house and detachment. But the first separation in the child’s life happens long before moving out. “Birth followed by ablactation, learning to walk, development of your own will (terrible two’s) etc. are milestones in the increasing independence from parents”.[3] It is a natural step on the way to autonomy to have your own apartment or a place in a living group. You as parents should be proud of your performance. You have managed to let your child go out to the world. Melancholy and fears can be mixed to this proudness: Melancholy, as a period of live ends, this intense parenthood won’t return, fears of changes in your own life and discomfort with the adult child.

„We make many transitions in our lives, but perhaps the one with the most far-reaching consequences is the transition into adulthood.”[4]

Detachment during youth is not only a time for development for the youngster, but also a time for learning for parents. “For both parties, detachment is a stage of dis- and new orientation and signifies identity crises not only for the child, but also for the parents.” „Unsolved detachment processes of youngsters restrain the new orientation of parents as much as unsolved new orientation of parents restrains the detachment of the young person.“[5]

4.1. Modifications within the family system – reset of parental role

Photo: Pixabay

"How can I fulfil my role as parent of a now adult child?" "What does the move-out mean for the rest of the family?"

Transition into adulthood and your child moving out mean an enormous change for parents.

„It would be ideal if both parties (parents and youngsters) had enough time to develop gently into different directions until all dependencies are loosened and contacts take place on absolute voluntary basis. This ideal detachment process is nevertheless very rare in reality, most of the time it is a period of heavy emotional distress“.[6]

Unfortunately, the right time seems to be very seldom. Either exterior living conditions such as a visit to a certain care centre or internal problems contribute to a too fast detachment, and parents have little time to adjust to this new situation, or children stay longer, some even lifelong in their parents’ house.

According to developmental psychologist Bronfenbrenner, if leaving is pending, this is understood as an "ecological transition" because "a person changes their position (in the ecologically understood environment) by changing their role, area of life, or both." [7] This always leads to a role change.

The reason for a possible crisis is that "children with disabilities are often central to their parent's life." 8] For years, everything was centred around one, and this role of the child also helps families to stabilize. [9]

When the child leaves home, it is particularly difficult for women to make the transition from active to passive motherhood, says Bettina Teubert, family therapist. The mothers feel superfluous and dispensable, and could suffer from an empty nest syndrome. A self-help group that makes it easier for mothers to transition and start working can help. " Empty nest is not a disease, but the consequence of normal life course with positive and negative aspects, but nevertheless the persons concerned often speak about „depression" and „grief work".[10]

When the child has left the parental domicile, it also may be that problems having been covered before appearing in their full harshness. For example, it may turn out that parents’ partnership is only through the child and their relationship has cooled down. Sometimes the father becoming is suddenly jealous of the adolescent and their freedoms mourns his own youth. And last but not least young people themselves find it completely unfamiliar to act on their own responsibility and decide, and they still have to learn it properly.[11]

If parents push the move-out due to external factors or as they seek a residential home for their adult child, they have to justify e. g. towards an administrative office that detachment is rather accelerated. “Springing into action for the detachment of a child has to provoke ambivalent feelings“.[12] „You have thrown your child out of the nest!“ If these feelings are not consciously treated this can lead to a problem. Discomfort with the situation can be transferred to the institution. “They do everything wrong.” (Uphoff 2018)

When parents and family members actively participate in this process, exchange ideas and learn to reorient themselves with increasing replacement, this phase can be well mastered.

If your adult child wants to live and stay with you for as long as possible, or if parents retain primary responsibility for them, redefining your own role and giving responsibility will also be important in order to reach a new equilibrium.

The following points can help in reshaping family structure and realigning roles:

- Active sharing in the family, developing common strategies, dealing openly with feelings and needs.

- Reflection of your own role, perspectives, needs, options for action.

- Discover your partner again, give space for the interests of other family members; siblings often put their needs behind them "automatically" for years.

- Exchange with other parents

- Enjoy common time with your partner and time for two.

- Let mourning happen. It is a normal symptom of change. Seek professional help if insomnia and other signs of depression are added.

- Stable social environment, good friends and family facilitate replacement.

- Finding new and old interests (again).

- Time for new projects.

- See also this checklist: Concrete Steps in the Separation Process for Parents

Unfortunately, we cannot deal with the situation of siblings the same way. However, due to the importance of the topic, we would like to point out that this particular relationship and its implications for siblings are being described in specialist literature more and more.

There is more spare time for new projects, hobbies or a good book.

4.2. Deliver support / find other supporters

„Everybody says I should let go, but nobody knows what my child really needs”.

This was said by a mother in a conversation about transition from parental care into residential living. It needs a lot of strength to let the child go anyhow.

Video: "How important are caretakers for me."

Every child is unique having an individual personality, their own wishes and different temperament. People with disability have limited abilities depending on the degree and level of their development.

Due to different kinds of disabilities and syndromes, special needs special provisions are necessary. A child with autism needs different support from a child with Down’s Syndrome. Whereas the autistic child can hardy maintain contact, young people with Trisomy have to learn, that it is not acceptable to fling your arm around everybody’s neck.[13]

Depending on the need of support, it can be reasonable to transfer certain fields of responsibilities to external support – nothing has to be permanent. The understanding of support can cover a wide range – from a simple expert tip to long-term social-emotional care.

Professional supporters cannot only help with self-development, development of independence and life planning, but they can also be a companion during rebuilding the parent-child-relationship.

For the splitting with or even fully transferring responsibility to external support there may be interim steps on the way to detachment. One possibility e. g. for a child with a high degree of disability may be to temporarily deliver the care at home to an external supporter, like a professional care service. First of all, this can be a discharge to have time for other necessary tasks and then as extension for free-time for yourself. This is linked to insecurity. Some processes may change, but it is a chance for the child too, to receive further learning impulses.

Another possibility is getting to know future supporters before giving up responsibilities. Confidence building requires time. It is important to give the necessary time both to yourself and others.

The active participation of the young adults with disability during the planning of their future living situation would be desirable. If the level of development allows it, they should be free to choose which living form, with which group members – and if possible –which assistants they want to live with in the future.

Such decision-making processes can only be successful if PWID have experienced an adequate right to co-management in earlier life phases.[14]

Psychologist Dr. Rüdiger Retzlaff said, „letting go is easier, if you receive something.“[15] If delivery of responsibilities to supporters is seen from this point of view, it is a relief for the parents and a chance for the child.

What may help you:

- Seek support among family, friends and professional organizations early enough.

- Take time to build up the necessary confidence.

- Take small steps in order to not overcharge yourself and your child.

- Take a look at the Checklist for vocational preparation.

4.3. Parents as legal guardians – Awareness of advantages and disadvantages

With their 18th birthday the child becomes an adult and can take their own decisions for themselves. This should be kept in mind, if e. g. a young adult can decide about his finances from one day to the another and be responsible for eventual consequences.

Adolescents as well as parents have to distinguish between parental authority and legal guardianship.

Extract from a law concerning legal guardianship in Germany (§ 1901 BGB):

(1) The guardianship includes all activities necessary to take care of all businesses of the supervised person in accordance with the following regulations.

(2) The guardian has to ensure welfare of the supervised person. Welfare of the supervised person includes the possibility to arrange his life according to his own wishes and conceptions in the frame of his abilities.

(3) The guardian has to respond to the requests of the supervised person, if this does not run contrary to his interests and if it is reasonable for the guardian. This concerns also requests which have been expressed before the guardian has been appointed – unless the supervised person does obviously not want to stick to these requests. Before handling important issues, the guardian talks these over with the supervised person, as long as they do not run contrary to his interests.

An adult with disabilities has the same rights as all other people but moreover, he benefits from more protection if the need for support has been stated by a legal authority.

Depending on disability and ability it may be wise to apply for a legal guardianship for some sectors only. These fields can be – depending on the needs of the supervised person - applied for a certain time only. Before the request for appointment is fulfilled, the wishes of the supervised person are considered.

In most of the cases, parents want to take over the legal guardianship for their child. If the child does not disagree with this proposal, the legal authority will appoint them as legal guardians as long as this corresponds to the interests of the child.

The parents should be aware before applying that guardianship can lead to interest and role conflicts: As legal guardians they have to decide for the benefit of the supervised. For this “benefit”, the legislative body provides a framework: the requests and conceptions of the supervised about the arrangements of its own life. This may differ from the conceptions of a mother or father, but anyhow it needs to be in a reasonable frame for externals. Is the person really endangered by certain actions? Parents may try to convince their children of their own conceptions of their life, other legal guardians may not.

There will always be cases in which legal guardians have to decide against the will of the supervised for good reasons. E. g. if a PWID is unable to handle money issues. Purchases via internet or contracts can be withdrawn by a clause of agreement. A contract for a mobile phone can be invalid and the mobile phone returned as a consequence. As parents you will feel the anger of your child and this may be transferred to other fields. If an external legal guardian takes over this task, the negative feelings will be addressed to this guardian instead of parents. Parents can rather offer comfort and reflection about the situation.

Care provisions that parents feel necessary exceeds extensively legal and decision-making authority of a legal guardian.

If an external legal guardian is appointed by the legislative authority, they have to act in cooperation with the supervised concerning expenses and other decisions. Should the supervised not agree with the decisions, parents are available as emotional supporters.

What may help you:

Reflect properly on effects of taking over legal guardianship may have on your children.

- Attend trainings for legal guardians, if you take over this duty.

- Find a legal guardian you and your child trust.

- Be there for your child, even if you deliver the legal responsibility.

4.4. Find support for yourself

Photo: Pixabay.com

Children’s growing up signifies an enormous change for the parents, too.

Children with disabilities usually have taken up a lot of space in family life. Therefore, it is even more important to find a new perspective after the children move out. To mourn about the past and to hinder changes do not help.

Especially mothers who have been occupied with the education of their children for a long time and thus haven’t been able to have a paid job, have difficulties to return to employment. They suffer more often from modified family situation than those in employment.[16]

You will find some helpful items below:

- Allow yourself to have space for your feelings. Take a day off, don’t cover your urgent problems and sorrows with jobs, but engage with them actively[17]

- Everything changes in life, so that people have the chance to grow. As parents, you need a firm self-consciousness

- Within your individual resources, you can find health, problem-solving skills, a basic optimism, humour, self-consciousness, emotional stability and many more. It is an important support for you to be aware of your powers[18]

- It is equally important to have contact with the supporters taking over care. With growing confidence in them, detachment becomes easier.

- It is good to restart unattended activities in order to fill your time

- Exchange with other parents, similar experiences often help. In difficult situations, a common concern can help you to orientate, to look forward and it has a stabilizing function“.[19]

- Take the chance to have expert supervision to “receive professional support for problems and their potential solution, or to speak with persons not directly involved in the situation and therefore able to have an objective view on the correlations“.[20]

- Every person has a right to leisure time and their own activities. Bad conscience about it is unfunded.

- Be aware of your own limits. In case of ongoing depression it helps to consult a competent therapists, so accept support when necessary.[21]

- Take a look at the Checklist for vocational preparation.

4.5. References

1 Spanhel, D. 2014: Erziehung zur Selbständigkeit in der Familie. In:https://www.familienhandbuch.de/babys-kinder/bildungsbereiche/selbststaendigkeit/ErziehungzurSelbstaendigkeitinderFamilie.php Zugriff am 10.05.2018

2 Fischer, U. (2006): Bindung und Ablösung bei schwer geistiger Behinderung. In: Bundesvereinigung Lebenshilfe (hrsg.). Schwere Behinderung – eine Aufgabe für die Gesellschaft! Marburg,S.281

3 Klauss, T. (2015): Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung – Ablösung vom Elternhaus (Winnenden 13 11 2015. S.37)

4 Heslop, P., Mallett, R. Simons, K. & Ward, L. (2002): Bridging the Divide at Transition. In: IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 17, Issue 3 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 41

5 Klauss, T. (2015): Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung – Ablösung vom Elternhaus (Winnenden 13 11 2015. S.64)

6 Sammer, U. 2004: Kinder werden flügge. Knaur. 2004

7 Bronfebrenner U. (1981): Die Ökologie der menschlichen Entwicklung. Natürliche und

geplante Experimente. Klett-Cotta, S. 43

9 Klauss, T. (2015): Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung – Ablösung vom Elternhaus (Winnenden 13 11 2015. S.10f)

10 Lempp, R.: Lebensphasen – Lebensorte. Schwierigkeiten des Erwachsenwerdens für geistig behinderte Menschen. In: Wacker, E./ Metzler, H. (Hrsg.): Familie oder Heim. Unzulängliche Alternativen für das Leben behinderter Menschen? Frankfurt/Main 1989, S.152-168

11 Teubert, B.: http://www.sueddeutsche.de/leben/empty-nest-syndrom-kinder-weg-krise-da-1.2588289-2 Zugriff: 28.02.2018

12 Sammer, U. 2004: Kinder werden flügge. Knaur. 2004

8

Klauss, T. (2015): Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung – Ablösung

vom Elternhaus (Winnenden 13 11 2015. S.10f)

13 http://insieme.ch/leben-im-alltag/erwachsen-werden/Zugriff am 20.04.2018

14 Senckel, Barbara (2015): Mit geistig Behinderten leben und arbeiten. C.H.Beck, München S.112

15 Retzlaff, R. (2010): Familien-Stärken. Behinderung, Resilienz und systemische Therapie. Klett-Cotta Verlag, Stuttgart. S. 245