Ageing

| Site: | ELPIDA Course |

| Course: | ELPIDA Course - English |

| Book: | Ageing |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 28 February 2026, 7:03 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Ageing process

- 3. Friendship and socialisation

- 4. Health

- 4.1. The starting point for building health in older years

- 4.2. Early signs of declining health in older adults with ID

- 4.3. Health checks preventing disease and disabilities associated with early ageing

- 4.4. Dementia

- 4.5. Pain

- 4.6. Challenges in health services

- 4.7. Information, conversations and decision-making

- 4.8. References

- 5. End of life

- 5.1. Definition and the European Consensus Norm

- 5.2. 13 norms to secure good care with life ending

- 5.3. Access to palliative care (1a-c)

- 5.4. Communication (2a-c)

- 5.5. Assessment of total needs (4a-d)

- 5.6. End of life decision making (6a-e)

- 5.7. Preparing for death

- 5.8. Grief

- 5.9. Bereavement support (11a-d)

- 5.10. References

1. Introduction

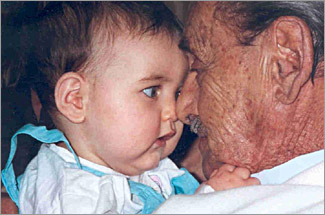

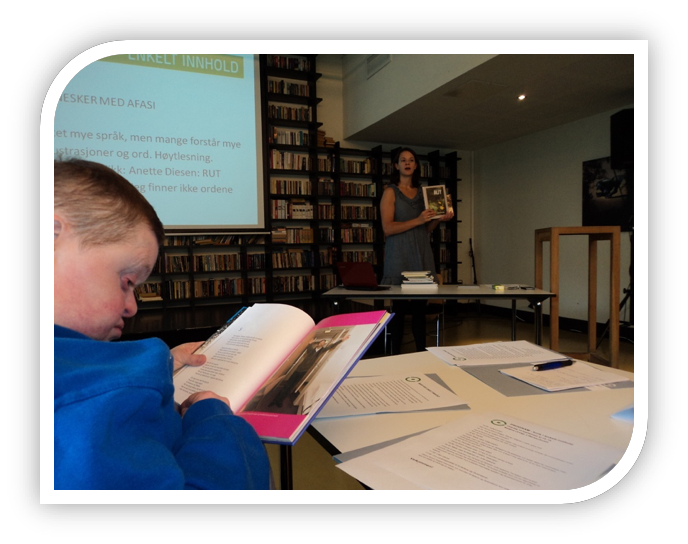

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

Before you start this sub-module, answer these questions for reflection:

- What do you think the ageing process means for people with intellectual disabilities (ID)?

- What are the main challenges for older people with ID, in general?

- What kind of support do you think your child/sibling/client needs for successful ageing?

- How would you communicate with your ageing child/sibling/client when it comes to topics such as ageing process, friendship, death and dying?

- How important do you think it is to talk about these topics and who have the responsibility to teach the ageing person about it?

In the need assessment [BW2] partners in ELPIDA conducted before the leaning-material was developed, only 11% of the survey participants said they had some training on ageing in people with ID. Most informants said they had very little knowledge (35%), or no knowledge at all of early signs of ageing (40%). These answers tell us that a special focus on early signs of ageing and unhealthy ageing process are important topics in this module.

At the end of the module, there is an evaluation [BW1] . We hope you take time to answer this so your answers can help us focus on knowledge you and others consider useful to increase and maintain a good quality of life for people with ID.

[BW1]Link to an electronic evaluation of the module

[BW2]link to the NA-report

2. Ageing process

Photo: www.who

Photo: www.who

In this chapter, you will learn about the ageing process from different perspectives and how people age in a successful manner:

2.1. Process of ageing

Older people create the clearest palette for personality and they become increasingly different from one another as they age. They become more and more like ‘themselves’. There is no one ‘right’ way for people to grow old (1).

|

|

|

|

|---|

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

People with ID, without major additional disabilities, have the same life expectancy as the general population. But it is a fact that persons with ID are more exposed to health problems and are often more vulnerable to developing psycho-social difficulties (2).

Reduced health and discounted functions result in not only a stressful situation for the person himself, but also for the next of kin. 'Double ageing' may be difficult, when parents and children get the ageing problems at same time (3).

Other challenges the person and their family may experience are:

- Lack of national (and local) senior policy that take into account retirement (less opportunities of life planning)

- Lack of support systems that follow up increased assistance at home (more burden for the family)

- Less network of friends and social participation (less opportunity to maintain contact with former colleagues and to establish new social contacts)

- Make a list of what you think will be most difficult for your child/sibling/client, when they become an old person?

- Make your personal list of what you think will be most difficult for your family (the service), when the person is old.

- Ask your child/sibling/client about strategies to cope with their ageing process, - reflect on answers you hear.

2.2. Ageing

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Ageing is the process of growing old, that implies various dimensions such as biological ageing, social ageing, historical ageing (4) and functional ageing.

The basis of the aging process is biological development - our cells are changing. In parallel with this, we perceive the world around us differently depending on which age stage we are. Everyone experiences life-phase transitions that may cause a shift in people’s functions and activities:

- The transition from work to a quieter life as a 'retiree'

- The transition from independence to increased need of help

- Transitions and loss/mourning experiences by close people’s death (family, friends…)

- The transition from independent housing to housing with service functions

Psychological processes of development and ageing from a lifespan perspective, the management of the dynamics between gains and losses, consist of three interacting elements: selection, optimization, and compensation (2:10). All three dimensions are equally important. It does not help to have a physically strong body if you have a severe depression that makes you lie in bed all day.

Functional ageing is a useful concept to describe ageing in people with ID. When adults with ID, at advanced chronological biological age, notice difficulty with walking, seeing, hearing, eating and talking, they may start to feel old (2:11). By focusing on 'functional ageing', the persons own understanding and feeling of being old are in focus. We listen to how the person himself define the ageing process and challenges they need help to cope with.

ACTIVITIES:

Discuss with your child/sibling/client about the functional ageing process;

- Describe an old person, maybe a person you know?

- What do you think is good when you are old?

- What are the most challenging issues about being old?

- How do you feel about your own ageing process?

2.3. Thoughts from people with ID about ageing

Often, PWID experience that other people are defining their life and life expectations. The social model emphasises people’s ability to discuss their life openly, which is essential for the influences, knowledge and concern society should have for the situation of people with disabilities: “… ‘who we are’ (are prevented from being), and how we feel and think about ourselves” (5:46).

Older people with ID have lived a long life and you may hear surprising thoughts about their life, even if you belong to their family and have listened to them before.

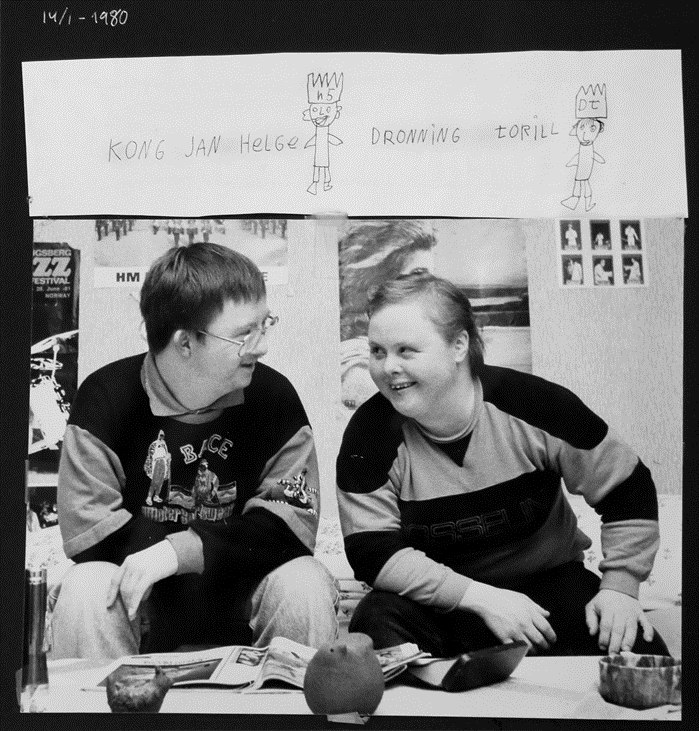

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

Lars Aage: What I primarily think in terms of growing old, is that we must never be spoiled by the wrinkles that comes in our face and above all, because this is a part of the charm and the process of getting old.

The other thing I think about, is that I have to think differently than I did before, when I was young, e.g. I need more help in daily tasks. Most people like me are offered public services, but this is gaining weight in the aging process, both in order to take their medicine and going out.

Ageing starts earlier when you have an ID. Therefore, we need help sooner than others. If it comes to a time in my life, when I cannot do any of the daily tasks or know where I am and what my name is, it is very necessary to go to a nursing home. I deliberately opted for group accommodation for my part, but this should be an opportunity for those who want such an offer. It is important to have all the possibilities - then choose. This is what I think now, but later I may think differently, that is my right to do.

It is important that people are taken care of and that you live in a safe place. It is important that you feel accepted as a person, a person who needs more or less help than others in the same situation.

It is important to get courses and easy-to-read information, material about the community's services and offers in the form of internet pages, booklets, info sheets and books. We are all different, so it is important that books cover different needs. For some, audio books are important. Accessibility in order to be a part of society is very important. This applies to both physical accessibility (e.g. elevator, wheelchair rampage) and easy-to-read labeling with symbols and icons (e.g. color marking) to public buildings and homes designed for disabled people.

It is important that people talk to us as adults, whether or not we have an ID. Talk straight to the person, look the person in the eyes and be in the same 'level' as the person e.g. take into account people who sit in a wheelchair or not understand difficult concepts or foreign words.

Now, when I am an adult and starting to be old, the most important change for me is the time I have for myself! I will decide the time myself! I want time to help others. I want to be with others in recreational activities and have more time with family and friends.

Torill: I notice my years now, and everything I have been through. Now when I'm older, it’s easier to forget what happened before. I forget more often. That's the memory I have now. I know I was good at remembering, but now it's not always so easy. Sometimes I’m stuck and do not 'get' the words I want to say. I'm now nearly 60 years old. But there are some good years left. I do not know how I will live. Death will be something new for me (6:34).

There are some myth about older adults with ID that may be wrong. Three of these myths are that older adults with ID:

- feel insecure about new situations and new tasks,

- are influenced by their painful past and so feel less confident because of this,

- like to relax most of the time.

In a Norwegian study, 75% said they like surprises, almost 90% liked to travel and over 50% liked to be active and to have many things to do every day (7). This study tells us that there is a gap between what people tell you about themselves and what others believe.

2.4. Successful ageing

Several people with ID do not know how to take care of themselves in a good way; they lack knowledge and ideas of how to do that. Several older adults depend on others for to be active, and sometimes family, siblings and staff do not have time being active together with them. The biggest threat to a successful ageing process is inactivity.

As a preventive measure 30 minutes or more of moderately intensive physical activity at most, preferably every day, is recommended for all adults. However, not every old adult with ID is fit enough to be engaged in moderately intensive physical activities (e.g. cerebral palsy). Some may be seriously hindered by medical conditions.

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

Parent’s age and ageing process influences their children. Parents’ retirement, sickness, death, relocation (to nursing homes) affect stability and choices. 'Unnatural addiction' to parents or other people affects the possibility of personal development and choice in children's own lives.

Retirement is a transition to a new phase of life. With increasing age and decrease of functions, it may be challenging to work the same way as before. It is important that the person should not feel this as a defeat. An individual plan for less working days or less hours every day is important.

Even if retirement offers time to do a multitude of daily activities and leisure activities that seem meaningful, many people with ID desire to work after retirement age. Some retirees even want to go back to work because they feel social isolated.

Everyone is different. It is always important to talk about ageing and retirement with the person in question. One conversation about ageing and retirement with Anne Marie, 59 years old, was like this:

Now, I will ask you about how getting older feels for you? What do you think of being old?

- I do not know yet, I ...

You do not feel like you are already old?

- No... I am not old, I

You do not feel like you have changed

- No - but in three years I will be 60 years old

How do you think Anne Marie will be retired?

- No, if you think it is up to me. I do not want to...

You want what you have today

- Yes, like now - and at the workplace

It's possible to be there if you are retired too – is it at the age of 62 or 64?

- 63 I heard... I am just sewing, you know

So you feel old?

- No

(9:162)

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

One tool that may be useful in conversation that also describes a kind of plan, is My days as old. This is an easy-to-read plan that anyone with ID, eventually with help from others, can use to describe their own thoughts and wishes after retirement.

The consequence of current research involves turning from a one-sided focus on the causes and effects of disabilities and diseases to more focus on individual characteristics of a good life; to live with the plagues and recognise the situation with disability and illness as well as good relationships, networks and the feeling of being appreciated and valuable. Persons with a positive focus on life live much longer than others do.

Factors that affect a positive life setting are the experience of managing your own life, self-insight, personality and relationships. People’s attitude determines the quality of life and life span to a greater extent than welfare and good health (10). Close relationships builds immune systems and preventive strategies for health (11).

According to science, the following factors are important for successful ageing (8):

- To be engaged in your own life and the society

- Learn new things

- Protect brain and heart by good choices

- Master stress

- Stretch and bend, build the body strong, work out balance, coordination

- Stimulate all senses e.g. dancing and listening to music

- Imagine you are young

- Have fun

- Learn from life (life story work)

- Find inner peace

- Be familiar with and live for your own values

- Find the love of life

ACTIVITIES:

- Read the list of successful ageing and connect this to your child/sibling/client situation, preferably talk about what you think they can change to get a better life?

- Find three of the most important factors for successful ageing you think your child/sibling/client will benefit from changing

- Find out together how these changes can be part of everyday life for your child/sibling/client - and perhaps for the whole family

2.5. Early signs of ageing and some consequences

The ageing process starts earlier for PWID, but it is not so different from the rest of the population. Even if ageing is an individual process, people with ID experience relatively large changes in Activity of Daily Life (ADL) skills after 60 years. For people with Downs, such a change already begins at about 40 years of age (9).

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

It may seem that more people with moderate and severe degrees of ID (depending on diagnosis) start the aging process up to 20 years earlier than others. Brain injuries and diseases reduced spare capacity and marks age changes earlier than others did. Other factors affecting an earlier ageing in people with ID are:

- Degree of ID

- Typical features of the syndrome or additional disability, e.g. Down's syndrome and cerebral palsy (CP)

- Progressive disorders

- Trauma and accidents

Early ageing has consequences for:

- When health problems in the ageing process start to make the debts

- Social life decline: retirement, friends die earlier ...

- Experience of quality of life

When you are together with the person every day, it can be difficult to discover the change in functions or early signs of ageing. First, when the person makes 'trouble', you may start questioning their health and life quality. Fast changes in a person’s behaviour or development of challenging behavior can be due to chronic illness, pain, lack of attention, etc.

Early signs on ageing are typically visual and hearing diseases and impairments, heart disease, diabetes and dementia that are more frequent among people with Down’s syndrome than others. Adults with Down’s syndrome experience 'accelerated aging'. They experience certain signs and physical characteristics that are common for aging adults at an older age. The reason for this is not fully understood but is largely related to genes on chromosome 21, as it is associated with the aging process.

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

At the same time, those with cerebral palsy (CP) have special health challenges that cause increasing problems already from 20 to 25 years of age. They may develop reduced muscle function, fatigue, pains, increasing cognitive difficulties, swallow problems and heart-lung problems. The risk of physical and mental congestion with further injury is great if it is not facilitated to get optimal follow-up early in the aging process.

In general, older age often causes health problems that need medical treatment. Polypharmacy is frequent in treatment of people with ID (12). Studies show that mental disorders increase with psychotropic medication. The impact of wrong medication frequently includes a restricted desire or ability to communicate and reduction in general motivation and attention span (2, 13-15).

We should be aware of the lack of knowledge about the medical effects of polypharmacy in persons aged 67 and over, as well as in people with brain damage. Medication may have other effects on brain injuries. This means that observation of medical treatment is crucial.

Usually, the experience of accelerated aging can be seen as medical, physical and functional. Family members and caregivers usually observe people with ID to seemingly 'slow down'. The complexity of this picture is that 'normal aging' in adults with ID is still not fully understood, and therefore it becomes more important to predict and prepare for the aging process. It requires more attention and mapping from the healthcare staff. It is important for the family to keep their eyes and ears open to early changes that make it possible to respond to these changes in a proactive manner.

ACTIVITIES:

2.6. The importance of good support - a preventive perspective

Throughout the world, there are studies revealing a growing ‘healthy’ cohort of people, mostly with mild ID, surviving to (biological) old age i.e over 70's (2). When people with ID are educated appropriately, they are more able to take care of themselves and may have more healthy and successful ageing. They need to learn productive coping and develop compensatory mechanisms during adulthood and maintain control over their life activities.

Photo: Lars Ole Bolneset

Prevention to improve the health and reduce the disability of older adults with ID, is important. Preventive health care for people with ID has received increased attention in the last 10 years, as evidenced by several international publications (2). A perspective on health objectives helps to ensure a systematic approach to some major issues involved.

Primary prevention is directed at reducing the occurence of new cases of defined health disorder by altering the risk factors. It implies strategies such as good nutrition, exercise programmes, healthy lifestyles, health promotion and education (2).

Secondary prevention involves efforts to reduce the prevalence of a defined health disorder by reducing its duration, by early detection and prompt treatment. Health mapping and proactive primary care are important. In this case people with ID are often given a passive and non-informed role, which should be avoided (2).

Tertiary prevention means to reduce the severity and disability associated with a particular disorder. The access of adults with ID to health services, adequate training of health professionals and others, their attitudes, and the quality and effectiveness of specialized services, are important for health outcomes (2).

It is important to provide support for a good friendship network and a self-governed life by social interaction, self-determination and freedom of choice. It is important to act quickly on morbidity when it occurs, promote health while taking into account health problems that accompany different disabilities and build good routines for health mapping and health care.

The most important thing is to have good knowledge of the person, mapping individual wishes and needs and have a good overview that you detect cognitive decline, physical weakness, poor appetite and less ability to take care of themselves early. By that, you may prevent serious changes to occur. Build good routines of health screening and health care, physical and psychically. Keep focusing on positive situations, relationships, happiness and personal development.

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

You can read more about about ageing in literature referred to in this module and at IASSIDD’s webpage: https://www.iassidd.org/content/aging-and-intellectual-disability-documents-and-publications

ACTIVITIES:

- Look at the model of prevention and ask what kind of prevention you can support your child/sibling/client with to improve their health and reduce disability in older age?

- Think of three things you think are the most important prevention strategies and ask your child/sibling/client what they think about it?

2.7. References

1. Hooker KS, McAdams DP. Personality reconsidered: A new agenda for aging research. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2003; 58(B): 296-304.

2. Haveman M, Heller T, Lee L, Maaskant M, Shooshtari S, Strydom A. Report on the State of Science on Health Risks and Ageing in People with Intellectual Disabilities. Faculty Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Dortmund: IASSID Special Interest Research Group on Ageing and Intellectual Disabilities; 2009.

3. Thorsen K, Hegna Myrvang V. Livsløp og hverdagsliv med utviklingshemning. Livsberetninger til personer med utviklingshemning og deres eldre foreldre. Tønsberg: Forlaget Aldring og Helse; 2008.

4. Haveman MJ, Stöppler R. Altern mit geistiger Behinderung: Kohlhammer Verlag; 2004.

5. Thomas C. Female forms. Experiencing and understanding disability. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1999.

6. Heia T, Westergård B-E. Venner Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2014.

7. Westergård B-E. Life story work - a new approach to the person centred supporting of older adults with an intellectual disability in Norway. A qualitative study of the impact of life story work on storytellers and their interlocutors. Edinburgh: Edinburgh; 2016.

8. Myskja A. Ungdomskilden. 12 gode valg for livet: JM stenersens Forlag AS; 2017.

9. Thorsen K, Olstad I. Livshistorier, livsløp og aldring. Samtaler med mennesker med utviklingshemning. Sem, Norge: Aldring og Helse; 2005.

10. Seligman MEP. Positive Psychology, Positive Prevention and Positive Therapy. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. p. 3-12.

11. Hart S. Betydningen af samhørighed – Neuroaffektiv udviklingspsykologi (The Impact of Attachment (2010), W.W. Norton). København: Hans Reitzels Forlag; 2006.

12. Walsh PN. POMONA II. Health Indicators for People with Intellectual Disabilities: Using an Indicator Set. Dublin: University College Dublin; 2008.

13. Hviding K, Mørland B. Rapport til Nasjonalt Råd for prioriteringer i helsevesenet; Helsetjenester og gamle – hva er kunnskapsgrunnlaget? En vurdering og formidling av internasjonale litteraturoversikter. Trondheim: Senter for medisinsk metodevurdering, SINTEF; 2003.

14. Patrick WHC, Kwok H. Co-morbidity of Psychiatric Disorder and Medical Illness in People With Intellectual Disabilities. Curr Opin Psychiatry, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007: 443-9.

15. Lyng K. Livskvalitet og levekår i den eldre delen av autismebefolkningen. Oslo: Autismeenheten; 2006.

16. IASSID. Aging and Intellectual Disabilities International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual Disabilities 2002 [cited 2018 13.06]. Available from: https://www.iassidd.org/uploads/legacy/pdf/aging-factsheet.pdf.

3. Friendship and socialisation

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Good friends are important

to feel love for others.

Together with them

I have a joy inside myself

I spreading out to other people.

It is a pleasure, good to feel,

for me and for others(1:74).

Torill Heia has Down’s syndrome and she was 57 years old when she wrote the book 'Friends'(1). together with me, Britt-Evy Westergård. In her book, Torill says that friends are essential for her to keep her active: “The radius of movement is less now, than it was before. Friends with ID, at the same age as me, get dementia and die”. Torill claims that friendships with different kind people, is one of the most important things in her life, she says: “Friends are love”. Her 'voice' from the book and from later collaboration, is used as references to illustrate the value of friendship in this chapter, as well as how this affects the life situation to older adults with ID.

Most people will argue that good friends are important for quality of life. Surveys and experiences indicate that friendship is not necessarily valued as a source of mental and physical health for people with ID. Health issues are more frequent in literature about ageing and ID, despite surveys showing that good relationships and friendships have a major impact on health and well-being.

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

It is not always easy to build or maintain friendships. There are differences in the lives of people who are in need of daily help versus those who are more self-reliant. Being dependent on help from others involves interactions that can be challenging for the one who receives help and the one who provides it. The value of friendship is the same for all of us anyway.

In this chapter, you will learn more about the importance of friendship and socialisation for older adults with ID:

- Ageing and social isolation

- Different kind of friendship

- Build and maintain good friendship

- People similar to ourselves

- Friendship to enrich life and improve health

3.1. Ageing and social isolation

Surveys show that older people with ID typically have a poor social network beyond the immediate family and paid caregivers (2-4). Up tp 40% do not have friends outside their own homes. By comparison, about 2% of the general population say the same (5). Results in this Norwegian study correspond to another one, including 14 women and 5 men, aged from 49 to 78 (average age 63). 74% of older adults reported that both of their parents had died. Only 31% had family members (siblings, aunts, etc.) they visited regularly. 35% said they did not have a single friend and none had a boy/girlfriend. Two people responded with a weak voice and with an expression that looked like shame and said that they did not know if they had any friends. One man said "I do not have a special friend, but it’s ok for me, I have my family" (6).

In countries where services for people with ID are at a lower level, more older adults live with their family, also after their parents die. In this case you will find differences between countryside and cities. Studies also show that older adults have smaller social networks than younger people with an ID. They lack a system of support when they grieve for friends and family who get seriously sick or die (7, 8), which is an important issue.

There are reasons to believe that older adults with ID are more exposed to loneliness, than older adults without disability. We do not know much about this; nor do we know much about their feelings/experiences of loneliness. We can assume that there is less feeling of loneliness among those who still live together with their family, even if they not have more friends outside the family. It also turns out that older people with ID are more vulnerable to end up without friends when those in their closest social networks die that is often the situation for those with older parents and siblings the same age as themselves.

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

After working together on the book 'Friends', I have reflected on how rich Torill's life is. One reason for this is her family. They have always encouraged her interests and kept in touch with friends who share the same interests as her, including sports events and music. When she sometimes calls me and I ask her what she has done the previous week, I think of how poor her life could have been without her friends.

ACTIVITIES:

- Ask your child/sibling/client how many friends they have and the quality of the friendship; how often they meet each other, what they are doing together and how they support each other?

- If your child/sibling/client wants more friends, ask what they want from this friendship.

- Ask your child/sibling/client how they want to work with friendship to get the best out of it. Discuss solutions.

3.2. Different kind of friendship

Most important is not how many friends I have

and who they are.

Most important is that they are good with me (1:10).

Torill and I have talked a lot about the quality of a good friendship and the importance of having different kinds of friends. Torill says that good friends help her to feel free to live her life. Together we have found out that good friends are usually, someone we have known for several years, people who:

- Have tolerated and encouraged us

- We feel relaxed with

- Understand us the way we want to be understood

- We feel comfortable sharing our inner thoughts with

- Share their life with us

- We have memorable experiences with

Both of us feel more friendship with someone in our family than with others. We think there are more people who have the same experience. Perhaps we feel like that because we are more accepted and appreciated by this family member.

Torill and I have many similar thoughts about our friendship. However, there are also differences between us. Even if Torill have lived an independent life, there are people who are deciding a lot in her life. This is okay for her, most of the time; she knows there are many things she needs help to manage. The need she has influences our friendship. We always decide things together; even I must take more responsibility when we are together. Because she needs more help now when she is older, there are many activities she is not able to perform independently, but together we do everything we want!

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

Photo: Britt-Evy Westergård

There is a difference between acquaintances and friends. An acquaintance is someone we may have grown up with, or someone we know from interest groups we have attended. Torill and I have attended the same sport and youth club. We know people from the same neighbourhood, which means that we have a common framework of reference when we talk about people we know. Usually Torill is the one that tells me news about our common acquaintances. This gives her an important social role in our friendship. Meeting acquaintances can become a source to have something to tell others: “Today I met ... it was nice ... do you know what he said ....”, - people who tells news, feel themselves important.

Peer support models prevalent in the general population also apply to adults with ID. Peer support efforts are social, emotional or practical help that people with ID can give to one another. Such models can facilitate understanding and provide support when, e.g. the effects of dementia are discussed, within the context of what adults with ID experience. Peer support efforts can also apply to aiding adults with ID who have become the cares for aging parents, spouses, and friends.

Torill says: "Some of my friends have disabilities, others not. I have friends in my family, neighbours and staff that help me in everyday life. I have friends from places I have worked at and schools I have attended. I have friends in football" (1:11).

Many of Torill’s friends have known her since she was in her teens. Her parents gave her confidence and freedom to go/bike around in the community. They encouraged her to keep in touch with people she liked. Eventually, the parents became so familiar with some of Torill's staff, that they spent vacations together. This period in Torill’s life, was very important and she talks about it with great pleasure. Karen Pedersen and Torill are still meeting regularly.

Torill says: "Karin Pedersen I got to know each other in 1981, I think. She is the staff I remember best from my first home… She is a lively girl. I have had good contact with her all the time. She invited me on holiday to Sørlandet the first time. Today, I have contact with Karin Pedersen when we meet at the cafe together with Karin Wessel. Karin Wessel did the washing at my former school and was one of the first staff in my housing. She has been at each of my birthdays since" (1:45).

s and friends. An acquaintance is someone we may have grown up with, or someone we know from interest groups we have attended. Torill and I have attended the same sport and youth club. We know people from the same neighborhood, which means that we have a common framework of reference when we talk about people we know. Usually Torill is the one that tells me news about our common acquaintances. This gives her an important social role in our friendship. Meeting acquaintances can become a source to have something to tell others: “Today I met ... it was nice ... do you know what he said ....”, - people who tells news, feel themselves important.Peer support models prevalent in the general population also apply to adults with ID. Peer support efforts are social, emotional or practical help that people with ID can give to one another. Such models can facilitate understanding and provide support when, e.g. the effects of dementia are discussed, within the context of what adults with ID experience. Peer support efforts can also apply to aiding adults with ID who have become the cares for aging parents, spouses, and friends.

Torill says: "Some of my friends have disabilities, others not. I have friends in my family, neighbours and staff that help me in everyday life. I have friends from places I have worked at and schools I have attended. I have friends in football" (1:11).

Many of Torill’s friends have known her since she was in her teens. Her parents gave her confidence and freedom to go/bike around in the community. They encouraged her to keep in touch with people she liked. Eventually, the parents became so familiar with some of Torill's staff, that they spent vacations together. This period in Torill’s life, was very important and she talks about it with great pleasure. Karen Pedersen and Torill are still meeting regularly.

Torill says: "Karin Pedersen I got to know each other in 1981, I think. She is the staff I remember best from my first home… She is a lively girl. I have had good contact with her all the time. She invited me on holiday to Sørlandet the first time. Today, I have contact with Karin Pedersen when we meet at the cafe together with Karin Wessel. Karin Wessel did the washing at my former school and was one of the first staff in my housing. She has been at each of my birthdays since" (1:45).

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Torill says: "The best friend, I have had for the longest time in my life, is Jan Helge. I have known him for over 40 years. He was an ordinary boy, about the same as me, with Down's syndrome … (1:36). Jan Helge was a little bit special. He was concerned that we should be fairly treated. If it did not happen, he clearly spoke up to the staff. We felt safe with each other and knew each other so well. We were so much together for many years" (1:37). 53 years old, Jan Helge died on August 14th 2011.

Photo: private

Photo: private

Photo: Lars A. Hynne

Photo: Lars A. Hynne

Torill says: "When I grew up, I had good friends in my neighbourhood. The best friends I had, were adults. Many were married couples (1:19). The neighbors taught me many things. At Gundersen’s I learned to play billiard, so I could play with the youngsters at the local discotheque. The youngsters thought I was good at billiard and they were happy when I won. When I won, I was gentle for the rest of that evening. When I did not win, I was a little depressed and not good to talk to (1:20). Robert and «Gundersen» (Geir Arne) are the ones I'm with when I meet other friends at sport. They are two former football players from Skrim. They take me to football and handball matches. Without them, it would have been difficult for me to see so many matches. They are awesome" (1:92).

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Torill says: "My best friend and only boy I have in my life now, is Tommy. Tommy is a cool man, gentle, nice and real. He also has Down's syndrome. I like that so much. Jan Helge and Tommy are the best friends I have had in my life. Jan Helge was more like a warrior, that is not the case with Tommy. Jan Helge enjoyed fighting, but that's not the case with Tommy. Tommy is too good, and he gets scared easily, so I have to take care of him. I comfort him…"(1:76-79).

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

When Torill describes her best friend today, people ask if Tommy is her boyfriend. Her answer to that is "we are friends and nothing more". Torill and I have talked about differences between friendship and boyfriend. Our opinion is that only those who are in the relationship, are able to give a good answer to these questions. Some may say that the boundary goes between sex or not, but this is not necessarily what Torill and Tommy think. Sometimes other people care too much and adds things to peoples’ relationship that is not right. This is sometimes devastating to Torill and other people in her situation. It is important to respect the way they define their friendship.

ACTIVITIES:

- Discuss with your child/sibling/client about what friendship is, you may use some of the examples from this page.

- Talk about where they think the limits goes between a friend and a boy/girlfriend?

- Find out if some of the friends your child/sibling/client have, can make agreements on activities they can do on regular basis?

3.3. Build and maintain good friendship

It's important to have time when we talk about life.

Time together brings friendship we feel safe in (1:12).

School, workplace or leisure activity are areas where one gets to know others and where the basis for friendship is often established. Many people with disabilities need help to keep in touch with their friends, both to contact regularly and to meet. Older adults with ID also say they need help in finding new friends (1, 6). Family, professionals or peers can help the person to participate in environments where there are opportunities for establishing friendships. They can also support friendship. However, there is little knowledge about the extent to which family or professionals actively assist people with ID, so that they can find new friends and spend time with friends they have.

When Torill is together with her friends, they sometimes meet people she does not know. When her friends tell her about their relationship, she understands that friends appreciate her. She feels like a valued person then. This makes her feel confident about getting to know new people.

It is often easier to have long-term friendships when we have common interests. Torill have had friends in her football club Skrim, for over 40 years now. These are some of her best friends. She says they are her friends because they want her to be social and experience life. It is realistic to think that sometimes friendship between people with and without an ID is based on the sense of responsibility and compassion, more than equal joy and respect.

Torill often experiences that people want her to feel good, for example, when they pay for her food when they are together. After we have talked about sharing and being equal in a friendship, she have discovered how surprised and happy others are when she sometimes pay for their food. She has changed her expectations for the meetings with her friends.

Establishing and maintaining good friendship requires skills in interaction and basic knowledge of themselves and perhaps expectations one ought to change. The family can have a facilitator and information provider role in this regard.

Establishing friendship is an investment of time, dedication and usually deep and close feelings for another person. Feeling good is perhaps especially important for people who are in a life situation where they are the 'receiver' most of the time. Being able to give something to people one appreciates, is also about discovering yourself, because one gets responses to their actions. We need each other to discover and confirm each other who we are.

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Torill and I agree that having fun is essential for good friendship. If the condition or diagnosis is prominent in the friendship, it becomes more of a commitment and responsibility for one of the parties, which makes it difficult to feel equal. One example is when Torill and I travel. I never tell her what she can buy or not. Once upon a time, I had to carry a bunch of CDs in my suitcase. Today this is a good story between us. When we travel, we are strong in each of our ways. She takes care of the time and I carry suitcases. At the beginning, it was a bit unusual for both of us, but after talking about responsibility for yourself as well as attention to each other's wishes and needs, we found a good way to cooperate. Such conversations require honesty, sometimes it is difficult to say things so clearly that the other one understands.

Torill and I have talked a lot about loyalty, friendship and love to other people. Torill says that this can sometimes be difficult. When your best friend fell in love with someone else, it can be difficult to continue as before. Torill says it is a bad feeling and you feel lonely. This is why it is important to be aware of what is happening between friends and support them finding good solutions before it becomes too difficult. Sometime people with ID solve conflicts best themselves, they find solutions that other people never would have thought about.

Torill says: "A best friend is a good friend for life. It's a friend who's there for many years and you become very familiar with. A best friend you can enjoy and give good hugs to. What is nice with good friends, is that we can argue without being afraid of losing each other. Good friends feel safe together" (1:36).

Life story work is another way to find friendships. In life story work, former friendship can be ‘awakened’. There are several stories about family members that found each other again after 20-30 years of no contact. Through life story work, people remember friends they had good moments together with and became more aware of people who loved them (6).

3.4. Friends similar to ourselves

People who have the opportunity to choose friends will choose people with something in common. Age and background may not have the most important role in a good friendship. Both Torill and I have friends who are either 25 years younger and 30 years older than we are. It is more important how we take care of each other and who we are.

The general lack of independence that most people with ID experience makes it difficult to find what others discover as their ‘niche’ influence, their identity. Self-expectations and self-identifications among people with ID, are often influenced by the expectations others have of them as a passive recipients or a person like others. The role they take, influence how they are categorised as prodigals or winners (9).

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

The basic understanding of motivated action and understanding is referred to in the empirical literature as the theory of mind. At the age of three and four the ability to interpret the actions of others and yourself starts. This skill is basic for an effective social interaction (11-13). Some people with ID have problems with interpreting social actions, and some of them learn this much later than at the age of three or four. Some people might never learn it. Especially people with autism finds mind reading difficult. The lack of understanding applies to the self as well and results in a disturbing dysfunction to formulate and convey sensible narratives of the self (12, 14).

Understanding differences and similarities are useful when we try to find a good friend or when we spend time together with them. Variability in human responses make us different and similar to each other. By looking at peoples’ traits, we find a number of similarities, influenced by people’s biology, genes and environment. Human responses and traits can be analysed from the following three perspectives (10):

- like all others,

- like some other persons and

- like no other person.

'1' Applies to some common features of humans and category '2' and '3' contain the differences between people.

Studies shows that there is a cortical explanation of differences in arousal levels between the extrovert and introvert types of personality. Introverts are more sensitive to any kind of stimulation: they tolerate relatively little social stimulation before they get an optimal level of arousal. Beyond this level, they start to withdraw to reduce the arousal (15).

In contrast, an extrovert person is ‘stimulus hungry’. An extrovert person will seek social stimuli and may have a huge social network. An introvert person may seek loneliness and prefer places with peace (home), while an extrovert person would prefer to visit places and people around the world.

If you are an introvert person, it may be stressful to have an extrovert person as you closest friend. You may be friends, but the time you spend together may be limited. Especially for people with ID, with serious communication difficulties, it can be difficult to avoid situations and people that do not fit them. Over time, this tendency may lead people to develop self-harming strategies as a way to get out of situations when ‘it all gets too much’. When introvert persons are together with friends, they do not need much action.

3.5. Friendship to enrich life and improve health

Good friends help us with life.

For us who have disabilities,

good friends are important. They can help us

to a life like everyone else and to do things we like (1:10).

Today people with ID are expected to be more independent and in control of their life conditions and daily life than previously. Having good social relationships can be more important for people with ID than before, as well as to be active, committed, staying safe and included.

While family members may have the best knowledge of the person, it does not mean that parents and adult children agree about the ‘best interest’ decisions. Often, the voice (empowerment) of a person with ID is lost in this dialogue. It is often easier to talk with friends about interests. Together with friends it is easier to go into new roles and styles.

Wolfensberger best known for pointing out that devalued people are given a role-identity that confirms and justifies the value society gives the person (16, 17). This is still an issue in our society.

Wolfensberger also believed that the most disabled need an alliance with people with more competence or people with a strong position in society. He pointed out that the only security people with disabilities may have is

“… whatever deep relationship commitments that have been made to them by others, and especially by people who do have competencies and/or resources, including those who are willing to share their last slice of bread with them.” (18:500).

A feeling of security is the basis for a good friendship and good public services. Establishing a good friendship is beneficial for both service providers and service users. Such relationships make it easier to talk about difficult things. Good knowledge and good feelings create respect that means to “look once more”. Respect, trust and good knowledge about each other, increases an understanding of reactions that otherwise can be interpreted as challenging behaviour or a part of a person’s ID (6).

Together with friends, you celebrate good times and get support during bad times. They help you prevent loneliness and give you a chance to offer companionship you need. Friends increase your sense of belonging and purpose; they boost your happiness and reduce your stress. Good friends improve your self-confidence and self-worth and help you cope with traumas, such as serious illness, retirement or the death of a loved one. Friends may encourage you to change or avoid unhealthy lifestyle habits, - or not! Friends actually play a significant role in promoting your overall health.

ACTIVITIES:

- Make a list of friends your child/sibling/client have, that you know will invite them to social activities when you are not able to support them any longer. If possible, make this list together with your child/sibling/client.

- Talk about the content of the list and talk about changes that can be done, - how and when?

- Discuss with your child/sibling/client about health and how friendship supports good health.

3.6. References

1. Heia T, Westergård B-E. Venner Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2014.

2. Brevik I, Høyland K. Utviklingshemmedes bo- og tjenestesituasjon 10 år etter HVPU-reformen. Oslo; 2007.

3. Jacobsen T. Vi vil, vi vil, men får vi det til? levekår, tjenestetilbud og rettssikkerhet for personer med utviklingshemning. Oslo: Sosial- og helsedirektoratet; 2007.

4. Tøssebro J. Velferdspolitikk. Trondheim: Nasjonalt kompetansemiljø om utviklingshemning, NAKU; 2010.

5. Söderström S, Tøssebro J. Innfridde mål eller brutte visjoner. Noen hovedlinjer i utviklingen av levekår og tjenester for utviklingshemmede. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning AS; 2011.

6. Westergård B-E. Life story work - a new approach to the person centred supporting of older adults with an intellectual disability in Norway. A qualitative study of the impact of life story work on storytellers and their interlocutors. Edinburgh: Edinburgh; 2016.

7. Brandt AM. Er jeg voksen eller er jeg gammel? - En mors tanker om sitt barns aldring og sin egen situasjon. Regionale konferanser om boliger for eldre med utviklingshemning – Helse øst; Oslo kongressenter: Utviklingsprogrammet aldring hos mennesker med utviklingshemning (UAU); 2006.

8. Thorsen K, Olstad I. Livshistorier, livsløp og aldring. Samtaler med mennesker med utviklingshemning. Sem, Norge: Aldring og Helse; 2005.

9. Gustavsson A. Delaktighet og identitet Norway: NAKU; 2012 [Available from: http://naku.no/node/904.

10. Kluckhohn C, Murray HA. Personality formation: the determinants. In: Kluckhohn C, Murray HA, Schneider D, editors. Personality in nature, society and culture. New York: Knopf; 1953. p. 53-67.

11. Baron-Choen S. Mindblindness: An essay of autism and theory of mind. Cambridge: MIT press; 1995.

12. McAdams DP. The Psychology of Life Stories. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5:100-22.

13. Wellmann HM. Early understanding of mind: The normal case. In: Tager-Fusberg H, Choen DJ, Baron-Choen S, editors. Understanding other minds: Perspectives from autism. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. p. 10-39

14. Bruner JS. The 'remembered' self. In: Neisser U, Fivush R, editors. The remembering self. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. p. 51-44.

15. McAdams DP, Pals JL. The Role of Theory in Personality Research. In: Robins RW, editor. Handbook of Research Methods in Personality Psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2007.

16. Wolfensberger W. The Origin And Nature Of Our Institutional Models. In: Kugel R, Wolfensberger W, editors. Changing Patterns in Residential Services for the Mentally Retarded. Washington DC: President's Committee on Mental Retardation; 1969. p. 59-17.

17. Wolfensberger W. Normalization: The Principle of Normalization in Human Services. Toronto: National Institute on Mental Retardation; 1972.

18. Wolfensberger W. 30 Concluding reflections and a look ahead into the future for Normalization and Social Role Valorization In: Flynn RJ, Lemay RA, editors. A Quarter-Century of Normalization and Social Role Valorization: Evolution and Impact Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press 1999 p. 489-504.

4. Health

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

In this chapter, you will learn more about the importance of discovering early signs of declining health in older adults with ID:

- The starting point for building health in older years

- Early signs of declining health in older people with ID

- Health checks preventing disease and disabilities associated with early ageing

- Dementia and pain, as two examples older adults are especially exposed to

- Challenges with health services

- Information, conversations and decision-making

4.1. The starting point for building health in older years

Photo: Laagendalsposten

Photo: Laagendalsposten

Most older persons with ID are strong and healthy survivors of their birth cohorts. They have experienced many historical changes in services they are depend of. Several of them have a background as institutionalised people, excluded from ordinary life in the society. Some have lived together with their family their whole life. The family have carried both the pleasure of having a person with ID in the family and the burden when a society avoids providing adequate social- and healthcare. A provision of health services that give support in:

- A healthy environment that prevent decreased health

- Identification of health risk early, including early signs of ageing

- Management of illness in an appropriately manner

- Preparation of appropriate palliative care and end-of-life decision-making

People with mild and moderate degree of ID need education and encouragement, while people with less ability for self-determination need high quality input. Input that satisfies their need of help and treatment, as well as information and practical support from their ‘persons responsible’

Effective training of health care practitioners influences the quality of health care directed to people with ID. To make it possible to discover early signs of illness and difficult situations, service providers and family members need to understand the importance of:

- Knowing the person well, especially those with major communication difficulties

- Building on the person’s understanding of their own body and health issues

- Recognising special features of illness

- Discovering early onset symptomatically increasing disability as they age

4.2. Early signs of declining health in older adults with ID

Persons with ID who survive and live into older age the combination of life-long disorders, their associated medications use and ‘normal’ ageing processes are at a greater risk for ill-health and an earlier burden of disease.

Low-income that limits access to healthy food choices, high energy (sugar) and low vegetable intake, some antipsychotic medications, lack of physical activity and a lack of health education all increase the risk of developing a broad spectrum of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular, pulmonary, metabolic and neoplastic diseases, osteoarthritis, need for anesthetics and surgery (1).

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

Lack of physical activity combined with dental ill health and inappropriate nutrition resulting in overweight and obesity are the most important preventable, modifiable risk factors. Efforts made at a younger age affect older years and enable people to develop healthy lifestyle habits that will ensure they continue to mature and age with a sense of well-being. Survival of people who have lost their mobility are poorer in later life than in the general population (1).

Early signs of declining health in older adults with ID more common than other health issues are (1):

- Cancer (see more information in chapter 4.7)

- Dementia; extremely early in Rett Syndrome and Angelman and frequent in Down’s Syndrome

- Hearing impairment, caused by chronic middle ear infections and ear wax blocking the canal, and a moderate prevalence for sensorineural and mixed hearing loss

- Hepatitis B, Tuberculosis and Helicobacter Pylori (HP) infections of people who had been formerly institutionalised

- Musculoskeletal pain

- Oral and dental health; i.e. gingivitis is earlier, more rapid and extensive with Down’s syndrome

- Osteoporosis and associated fractures

- Overweight and obesity

- Side effects of drugs

- Unprocessed trauma of abuse and violence

- Vision problems i.e. refractive errors, strabismus, cataracts, and kerataconus, hyperopia, myopia, and astigmatism

Some say that all persons with severe and profound ID and all older adults with Down’s syndrome should be considered as visually impaired until proven otherwise. In older adults with ID in general the vision impairments are more severe because of pre-existing childhood onset visual pathology and other co-existing sensory and physical impairments (2).

Older adults without a lifelong vision impairment may not be well prepared to manage their impairment in older age. Absence of education, rehabilitative efforts or changes in the physical environment to cope well with their vision problem, may get more consequences than necessary. Family and staff, are often not sensitive, experienced or informed enough to deal effectively with significant regression of vision and hearing function (1).

Older women with less severe disabilities and those with certain syndromes i.e. Down syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome are more likely to be obese, compared to their counterparts. It may be difficult to build a healthy lifestyle when there is stiffness and pain in the body because of ageing. Therefore, pain assessment is important in older age.

Cardiovascular diseases are less confirmed and people with ID have relatively low rates of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. At the same time, cardiovascular disease is reported to be the primary cause of death for people with ID in most western countries.

Early signs of declining health, especially in older adults with Down’s syndrome are:

- Altered T-cell activity and tumor, with increased risk of leukemia

- Alzheimer's disease, frequency of over 50% after 60

- Atlantoaxial and Cervical Spine, watch this video for more information (19): https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=MLhcA6Ngrmc[BW9]

- Coeliac disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Epilepsy

- Immune system pathology, There might be a relationship between recurrent infections and higher risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses (1)

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Osteoarthritis

- Osteoporosis

- Thyroiditis

Early signs of declining health, sometimes already from 20-30 years of age may occur in adults who are non-ambulatory i.e. with cerebral palsy, permanently reliant on using wheelchairs for mobility and persons with severe and profound ID (1, 3):

- A marked decline over 60 in deterioration of muscular function; exacerbate already low Bone Mineral Density scores with potential consequences for early onset of osteoporosis and brittle bones

- Cardiovascular disease risk factors

- Depression

- Increasing cognitive difficulties

- Overweight and obesity, BMI more than 27

- Problems with swallowing - feeding and posture

- Respiratory disease are thought to be mainly due to pneumonia and aspiration, normally associated with Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Risk factor for constipation (obs specific drugs)

- Type 2 diabetes

Studies shows that persons with severe and profound ID have lower rates of hyperlipidemia, overweight and obesity, type 2 diabetes and there were lower rates of hypertension compared to persons with mild and moderate ID. We also assume that smoking is less common in persons with severe and profound ID.

A perception of good physical health is associated with good mental health. Subjective well-being and personality influences the person’s perception of mental and physical health.

People with a severe degree of ID have a three to four times’ higher probability of experiencing mental problems than normal population. At the same time, it is assumed that persons with a mild degree of ID have one to two times’ higher probability than people with a moderate degree of ID. There is, however, a divergence between studies of mental health (4, 5).

Connections between life events and mental problems are well documented, so is the correlation between depression and unpropitious life conditions (6). People with a mild degree of ID with essential features for being integrated may feel they have to hide their disability and their past e.g. the feeling of shame of growing up in an institution (7). Such situations can lead to an unhealthy and stressed state, especially if this is their daily issue. Growing up in an institution also involves a high risk of stress, which may lead to psychological difficulties (4).

ACTIVITIES:

- Reflect on the diagnosis your child/sibling/client have and connect this to the risk of early ageing; what do you think the highest risk of declining health in this case is?

- The most important thing is an assessment of health that can be done by persons close to the ageing person. How can you observe early signs of health issues in your child/sibling/client and how can you involve them in this assessment?

- Discuss with your child/sibling/client about the importance of taking care of own health and pointing out places in the body that hurts.

- Ask your child, sibling or client about their daily life, and if there are situations or people that stressing them. Do they feel happy, sad or angry most of the time? What makes them feel happy, sad or angry?

- Ask your child/sibling/client about their cooping strategies to feel satisfaction in their daily life.

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

4.3. Health checks preventing disease and disabilities associated with early ageing

The World Health Organisation (WHO) have adopted the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF 2001), a comprehensive review of health status seen from a biological, personal and social perspective (8).

The tendency for people with ID is that they are at risk of being diagnosed late in their disease trajectory, due to lack of screening or ‘diagnostic overshadowing’. Health problems that may have been present since childhood are likely to remain undetected, thereby increasing the chances of impaired learning, communication and personal development (9). There are examples of older adults with ID, using the same medication they started with when they were children or youth. Since the body change when we age, the conversion of the drug in the internal organs becomes slower and the risk of overdose and poisoning is greater.

Diagnosis that overshadows/dominates other signs of health problems are:

- Behaviour or challenging behaviour are interpreted as mental illness and not as their way of expressing physical discomfort.

- Medication for mental disorders can camouflage bodily ailments.

- Dementia makes it difficult to discover other disease signs.

- Communication problems.

- Indifference/discrimination: Negative attitudes among health professionals, lack of experience and cooperation.

- Service providers/family members who lack sufficient competence to detect signals on illness.

- Lack of organised screening surveys.

- Waiting too long to consult a doctor.

Regular health checks for people with ID have a major effect and reveal undiagnosed conditions, ranging from severe disorders like cancer, heart disease and dementia, to conditions such as hearing impairment and vision.

The proportion of undetected hearing and visual impairment is especially large, even among people with mild and moderate ID. Reversible changes in hearing function are often neglected by staff members/family who are in direct contact with the person. For many, but certainly not for all, removal of earwax is a solution to the problem.

Regular health control is a health preventive measure: symptoms and findings treated before they cause health damage and loss of function. It provides a better health follow-up of each person, and an opportunity to capture signs of functional disorder or illnesses as early as possible during the process.

Preventive health care is important and can save the individual from unnecessary suffering and society from unnecessary expenses. A thorough first-time survey will provide a good basis for registering changes and initiating treatment measures. A first-time functional check should start when people are in their mid/end of 30’s and followed up regularly so that an individual profile is developed.

Health assessment measures for people with ID are mainly based on reports from staff or family members. However, you will also find health assessment measures that are user-led and encourages self-reporting.

Some videos that shows adults with ID accessing important health checks are:

Health Check Resources for Adults with Learning Disability (20):

A guide to your LD health check - for adults with learning disabilities (21):

4.4. Dementia

Dementia is the syndrome of progressive memory loss, other cognitive loss, epilepsy and behavioural change that occurs with pathological deterioration of the brain. In advanced stages primary body functions are also affected, such as loss of vision and speech, incontinence and mobility (9). There are more than 100 diagnoses under the umbrella of 'dementia'.

Amongst the population with ID, there are some genetic syndromes associated with extremely early dementia – e.g. Rett Syndrome, Angelman Syndrome. It is well established that people with Down’s Syndrome develop Alzheimer’s Disease (the most commonly diagnosed cause for dementia) at a younger age than the general population (1, 10).

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

Photo: Jørn Grønlund

There is also evidence for increased prevalence of dementia in people with ID over the age of 65 years without Down’s syndrome as compared to the general population. This is possibly because of the earlier age of onset (1, 10).

Approximately 46 percent of persons with Down’s syndrome aged 50+ have epilepsy and late detection is often related to early signs of Alzheimer disease (11). Age of onset is in the mid-50’s and the prevalence increases until the age of 60, after which it appears to drop. This may possibly be due to increased mortality associated with dementia (10).

Studies suggest that changes in personality and behaviour in mid-life with no other explanation could be very early clinical markers of dementia that become apparent some years later (9, 11).

You can learn more about Alzheimer's disease from this video (22):

(22):

Compared to people without ID, characteristics of each stage in people with ID, are different. Common signs in the three stages of dementia in people with Down’s syndrome are:

Early stage - mild or moderate degree:

- Loss of memory

- Disorientation

- Reduced verbal language

Early stage - serious degree:

- Apathy

- Inattentiveness

- Reduced social interaction (ref. Frontotemporal)

Intermediate stage:

- Loss of ADL skills

- On / off dressing, toilet, eating etc.

- Restless walk

- Seizure

- Reduced work skills

Last stage:

- Immobility

- Stiffening

- Incontinence

- Lack of reflexes

The last 6 months:

- Serious memory loss

- Changed personality

- Highly reduced orientation

- Incontinence

- Seizure

- Complete functional loss of own skills

To be a family to people that develop dementia means feeling of loss, grief and worries. Especially for those who are taking care of the person at home, burden on the family can be almost prohibitive.

There is not much knowledge of experiences family, friends and carers of older adults with ID and dementia have, including those from minority backgrounds. However, it is believed that family members and carers need training in dementia care, and they need support.

Perspectives of adults with ID is also limited to subjective experiential information available from them. Almost none is available on personal perspectives drawn from research. However, the film 'Supporting Derek' (23), gives a certain understanding.

Other sources about ID and dementia can be found in Karen Wachman’s webpage: http://www.learningdisabilityanddementia.org/publications.html. In this webpage you will find Jenny’s Diary, a booklet and a set of postcard you can use supporting conversations with the person with ID and dementia. The booklets are translated into languages this course ELPIDA also use: www.learningdisabilityanddementia.org/jennys-diary.html.

ACTIVITIES:

- Find out what risk your child/sibling/client is at to develop dementia, look at diagnoses and the frequency of dementia in the family.

- Find out if there are easy-to-read leaflets about dementia in your language, use these leaflets and discuss with your child/sibling/client about dementia. Give examples that are familiar and people they know well.

- Look at the environment your child/sibling/client lives in today, do you think this is proper environment if the person develops dementia? What can you do with the environment and facilitation of welfare technology?

4.5. Pain

Pain is a subjective and comprehensive feeling, and if you know why it hurts, the pain is easier to handle. There is less knowledge about how elderly people with disabilities express their pain. Pain is almost a non-existent topic in literature on older adults with ID.

Recurrent acute musculoskeletal pain is a frequently reported symptom in older people, as is pain in other organ systems, related to ageing of those organs. Additionally, it has been postulated that the ageing brain may experience more pain (1). It is a higher proportion of women that have chronic pain (12), and cerebral palsy has a clear physical influence on premature ageing, which often causes problems with pain, concentration and immobility (13).

Chronic pain is overlooked and untreated, especially in people with inadequate communication (12).Chronic pain in adults and elderly with ID is more common than previously thought. Acute pain can become chronic and psychological causes must always be investigated. Regular medication with analgesic can make it difficult to diagnose the degree of pain in people with ID (1).

Pain that is not recognized, or poorly managed, can affect the quality of life. Studies show that pain is not often on the checklist of health personnel and not something the family or closest providers consider when they assess health status and behaviour change (1, 14). Ordinary health service staff lack practice and knowledge in how to communicate with and understand persons with ID. This can result in the mainstream health system to provid poor services and there is a constant inability of health services to properly detect pain or diseases in those with ID (14). For some years, there are developed assessment tools for pain for persons with ID. However, even today these assessment tools are still in the stage of development.

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

Photo: Lars Aage Hynne

While persons with mild ID, who have potential communication skills, need to be educated in the effective communication of pain or distress, the family and staff need to be able to recognise signs of pain and distress in persons with severe ID and limited verbal capabilities.

When people with ID are unable to communicate with words, they express their pain in other ways:

- Adaptive behaviour, i.e. rubbing of the affected area, avoiding certain movements

- Autonomic changes, i.e. increased/decreased pulse, blood pressure, sweating

- Facial expressions, i.e. grimacing

- Hyperactive behaviour

- Self-injurious behaviour

- Self-distracting behaviour, i.e. rocking, pacing, biting hand, gesturing,

- Sleep disturbance

- Vocal responses

- Withdrawal, low mood

ACTIVITY:

Watch the video about identifying and assessing pain (24). When you watch the video, ask yourself if your child/sibling/client have any symptoms of pain and what you can do about it.

4.6. Challenges in health services

People with ID are generally frequent users of healthcare and require access to universal health services used by the non-disabled population, even when they have complex health needs and experience inequalities that contribute to their premature, and often preventable, deaths (14).

Healthcare practitioners in universal health services often lack the knowledge, confidence and skills to recognise and manage the health issues experienced by older adults/people with ID. In hospitals, doctors and nurses lack knowledge of 'diagnostic overshooting' that means that they attribute the problems to developmental impairment. They often do not understand the person’s way of communicating and are not responsive to parents and support staff expressions (14). Watch the video below and listen to what Amanda says about her experiences (25):

Impaired communication skills are one of the most important factors affecting assessments and procedures in connection with hospitalisation of people with ID. Communication ability has a decisive effect on both treatment processes and hospitalisation results (14). A consequence is that family and closest staff are worried about the person’s health. They may be uncertain of the health care system’s ability to provide efficient and good health treatment. Not everybody experiences lack of health competence, but one bad example is one example too much. A very tragic story in this field is the ‘Jayne and Jonathan's story (26):

There is evidence from several European countries that the number of people with ID are under-represented in hospice and palliative care services (15). One explanation can be that more of them live in group-homes that also provide healthcare. Family also plays a crucial role in supporting older adults with ID to ‘age in place’. Families face many challenges in this field:

- Caring for themselves and their child/sibling as they both age

- Constant fear/anxiety of who will provide care for their relative when they can no longer do - a lack of planning from the local community

- Dependence on informal support and greater need for formal support

- Mutually dependent relationships

- The effects of long-term caring

In recent years health professionals have focused on their lack of competence on people with ID. In Europe, especially in the UK, several places have developed tools that can provide better support when people with ID arrive at a hospital. One example is ‘This is my Hospital passport’, a resource for people with ID or autism who need hospital treatment. The passport is designed to help them communicate their needs to doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals.

Despite the evidence-base, health action planning is limited. In the UK individualised health action plans (HAPs) are currently being promoted by the government. HAP set out the person’s health problems and health needs, linked with regular health checks. Although the person with ID is involved in developing and keeping the action plan, the responsibility for maintaining it and facilitating the actions required lie primarily with the person’s helper (health advocate, carer or health facilitator).

ACTIVITIES:

- Find out if the country where you live have recommendation on health checks especially for people with ID. If the answer is 'no', what can you do with it?

- Discuss with your child/sibling/client about the importance of regular health checks, and how it can be done.

- How can you support your child/sibling/client in regular health checks?

4.7. Information, conversations and decision-making

Many older adults with ID never attended school. They have limited knowledge about the ageing process and their understanding of the mechanism of physical illness may be limited. Most of them do not understand their body functions and lack the ability to communicate bodily changes and sensations.

Terminology in biological and physiological explanations e.g. in treatments, may be problematic for people with ID (actually, for others too). Medical jargon and concepts are abstract and quite complex, and lack of communication skills easily lead to dependency.

In this video, you can hear people with ID in the self-advocacy group ‘My Life My Choice’ talk about their experience of ability related to health checks and health services (27):

HealthWatch from My Life My Choice on Vimeo.

When people get sick and need professional help there are many decisions that have to be made. Opportunities’ for self-determination depend on peoples’ knowledge and the information they receive to make decisions.