Transition to adulthood

2. Understanding my child

2.3. Specialities by PWID

Photo: Pixabay.com

For adolescents without disability, a desire for autonomy and independence is usually supported by the parents, and they become gradually equal. Many parents find attempts to gain power, personal responsibility and self-determination by a child with ID stressful, especially when it is accompanied by difficult behavioural patterns.

Many parents find it difficult to accept the child as an adult, because their linguistic and cognitive skills do not exceed a child's proficiency level. This makes it harder to develop more autonomy. The danger is a fixation on the level of "eternal childhood". [14] The fact that many PWID is not trusted to live an independent life is also often due to the fact that they could not sufficiently initiate and try it out. Because of cognitive limitations, the self-assessment of the adolescent is often less trusted: sometimes boundaries are vigorously enforced. The danger that the adolescents are being tightly controlled is very high. [15]This chapter gives you an overview of specifics of how a person with ID (PWID) grows up. We believe the following points are especially important:

Development stages are non-contemporaneous (2.3.1.)

Cognition is missing as a resource (2.3.2.)

Replacement symptoms are not always recognizable as such (2.3.3.)

Physical maturation as a development opportunity (2.3.4.)

The peer group as a social resource (2.3.5.)

The drive for replacement is fragile - the importance of special dependency (2.3.6.)

2.3.1. Development stages are non-contemporaneous

Photo: IB Sued-West gGmbH

Like everyone else, PWID undergo the physical aspects of puberty. This is basically the same as with others, but maybe its timing is different. In these cases, puberty sometimes starts up to 5 years later and often lasts longer. Mental and emotional development drifts apart.

The psychological structure of PWID does not deviate from non-disabled people in principle. Thus, every maturation feature of an average person can also be observed under certain conditions or at certain times during the development of a PWID. [16]

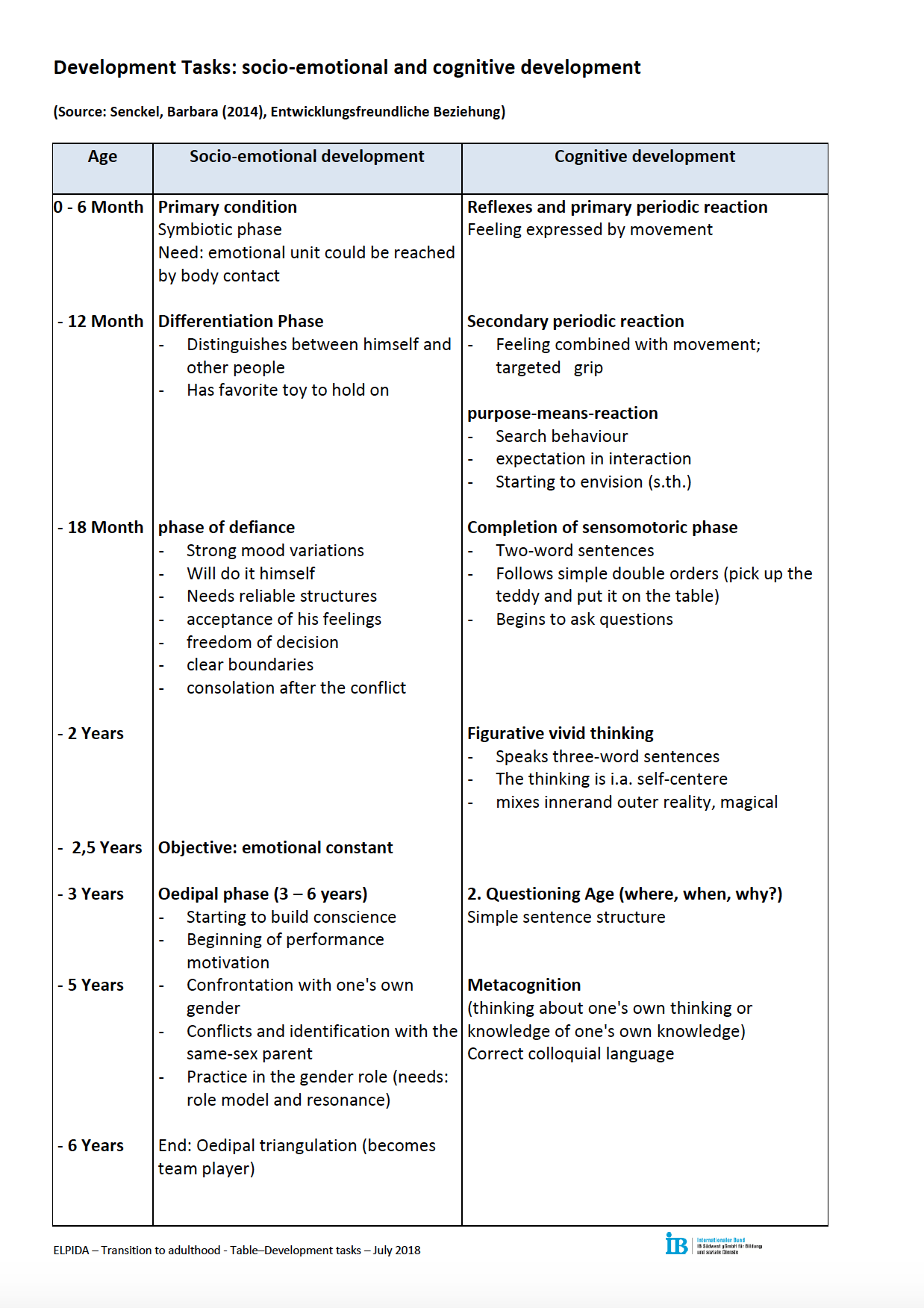

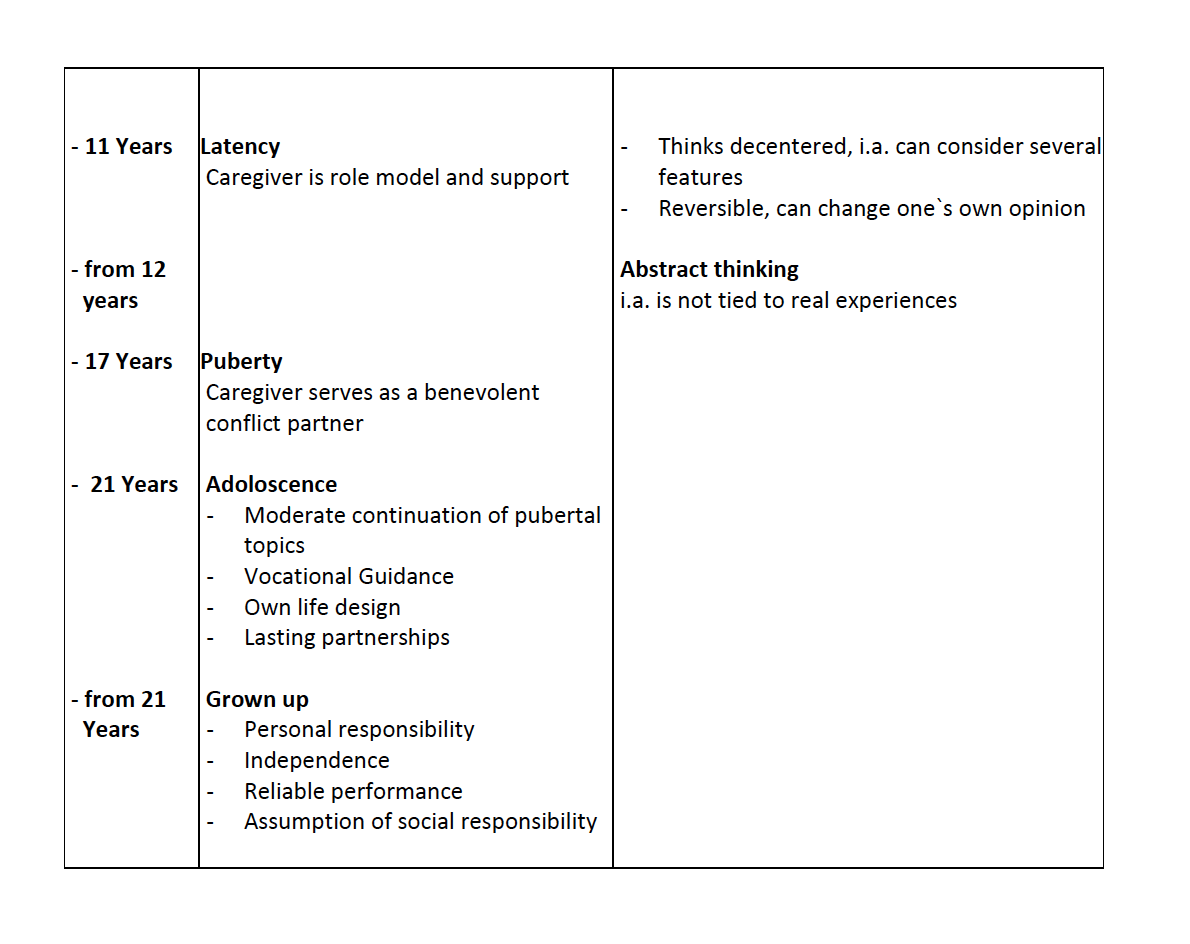

It is key not to consider cognitive advancement on the whole as a measure of overall development. "The need to detach from the parents during adolescence and to achieve a degree of self-reliance as a child is a maturing task, which is largely independent from intellectual advancement." [17]Child development scoring matrix measures two developmental areas - the socio-emotional and the cognitive:

Parents and carers can check the development level of the PWID by trying to use the table to determine first cognitive, then emotional age. The person should be encountered at the respective stage of development and the different development areas should be strengthened separately, so that the person can reach the next stage of development. [18]

2.3.2. Cognition as a resource is missing

Abstract thinking helps to process experiences and arrange them for yourself.

A primary school aged child can e.g. think logically about reasonable problems and review the experience. But it always relates to what they see or experience in the here and now. It is only during adolescence, that the ability to think abstractly is fully developed. The child can now derive logical consequences based on theoretical principles.

For PWID the ability of abstract thinking, depending on the degree of disability, is less pronounced. The opportunity to reflect on the change taking place is often not given.

The hormonal side effects of puberty such as mood swings, sudden outbursts of anger or new reactions of the milieu to expressions of your own will often cannot be well-managed by intellectually disabled people. They often feel helpless experiencing them. [19]

Adolescents also perceive limits clearer, that are often associated with painful processes. E.g. a PWID attending an integrated school: growing cognitive discrepancies become more apparent and adolescents of the same age withdraw. Being different is experienced painfully by the adolescent. They feel increasingly marginalized and increased rivalry can be even more problematic.

Another example is an adolescent who grew up in an institution. They are more likely to suffer from the limits set in this environment and want to live free as "normal" youth. However, everyday life is often relatively structured and designed for living together in a larger group. The individual desire to dissociate and expand can often be less realized in this context.

Whatever boundaries teens may struggle with, it can lead to emotional frustration and injury. These are then often reacted on with aggressive, regressive or depressive behaviour. [20]

Photo: pixabay.com

2.3.3. Detachment symptoms may not be recognized as such

"The obvious and covert detachment and impulses of being self-sufficient by adolescent or already adult daughters and sons are often classified by parents as disability-specific problems and are neither understood, nor supported as necessary maturing steps on the way to be a grown up.Detachment handicap is a factor that get far too little attention.” [21]

It is important for adolescents with ID, that caregivers take their changed behaviour seriously and as a positive sign of development. That is not always easy. Thus, e.g. rule violations or denials are understood as a "simple" discipline problem, even though the young person is trying to gain new freedom for themselves. Especially when linguistic development make debate limited, it is difficult for both, parents and children to understand what is going on.

However, when it comes to the issue of replacement and a caregiver does react, the teenager becomes more helpless than before. Sometimes they only have anger or resignation and withdrawal. If they are not understood in their attempts to detach themselves, youngsters will not receive support for cutting the virtual umbilical cord.

What this means and how you can detect detachment symptoms as such is described in Chapter 3.1.1.

2.3.4. Physical maturation as a developmental opportunity

"Even severely disabled people who do not exceed the mental development level of a three-month-old infant show emotional hormonal side effects of puberty. ... Even a spiritual awakening can be observed with the severely disabled ... Thus, even for a mentally disabled person puberty is a time of upheaval that influences the overall personality and opens up new opportunities for development. However, which development steps can actually be carried out depends on the type and degree of disability." [22]

Dr. Senckel emphasizes that physical development can be an engine for social development, even with persons having complex disabilities. It is important to perceive and support this. She reports on a severely disabled man, who refused to be touched until his mid-20’s. He changed this behaviour at the beginning of his puberty. He made contact with other people, even timidly reaching for his caretakers. Nobody trusted him to do this earlier on.

Physical changes unsettle some PWID so much that they largely ignore them. For example, some girls wear extra-large sweaters when the breasts start to expand in order to conceal them.

Time of change also in neurobiological area:

A reconstruction of brain tissue takes place among other neurological phenomena during adolescence. Thus, with the onset of puberty, many nerve connections within the brain that are no longer used are dismantled. Grey substance, that forms the nerves of the cerebral cortex, reduces measurably and white matter that is responsible for the rapid exchange of information, increases. The juvenile brain increases its computing power up to 3000 times. Adolescents forget unused or unsolicited matters and become more responsive in their attention and decisions. [23]

2.3.5. The peer group as a social resource

Photo: IB Sued-West gGmbH

The peer group is also an important resource for the development of puberty and adolescence for intellectually disabled adolescents.

"Within the peer group disabled young people are establishing their status; there is a strength measurement against rivals: aggressive confrontation and submissive serfdom are not unusual. But it can also develop sustainable friendships, so that new forms of social behaviour can be learned. Of course, with the sex drive also the interest in the opposite sex awakens. Here, too, the longings are like those of the non-disabled. A successful friendship makes an important contribution to the development of identity; not replaceable by adults." [24]

However, this resource is more difficult for them to access. These young people are usually limited in their mobility and independence. They find it harder to build and maintain relationships with the peer group outside of the family and school. In addition, contacts usually take place under supervision and are usually regulated by reference persons. It is also harder for them to engage in and use social infrastructures in their local environment. For example, they are not welcome at local youth club.

A particular difficulty for adolescents with disabilities is that they are often dependent on their parents or other caregivers for encounters with the peer group. They are less exposed to risks, but also have a limited field for practice. They live with a contradiction: meetings with the peer group as a support to the detachment from the parents must be accepted and accompanied by the parents. [25]

More about the meaning of the peer group and how you can support your child in Chapter 3.1.2.

2.3.6. The drive to detachment is fragile - the importance of special dependence

"What would happen to a person without detaching from the family? How many of them does still live with mother and father, are dependent on them and limited to the immediate living environment of the family? Who is their ideal if they live such a life?” [26]

Adolescents with disabilities want to get rid of dependency from the parents. This means they have an urge to go outside and friends become more important. At the same time, they depend on family support in many aspects. They need support in everyday life, bodily care, maintaining social contacts and much more.

"As far as attitude towards your own wishes and abilities is concerned, many adolescents with disabilities have ambivalence: on the one hand they want more independence, self-determination and autonomy; they also want to live "like others"; but the more they become aware of the fact that they depend on the support their parents offer them, the more they feel they are losing this safety." [27]

The care of the parents was and still is vital.

This ambivalence pulls them back into the family circle. Young people with mental disabilities are even more affected be this tension than others. The drive for detachment is thus very vulnerable.

Parents are aware of their child’s dependencies and these do not resolve by themselves because a pubescent teenager no longer wants his parents. [28] In this respect, the child with intellectual disabilities is also dependent on the parents in the matter of separation: the parents themselves must deal with detachment and also develop new future perspectives for themselves.

This raises the question of who should provide the necessary support for the child in the future. Parents are often the ones who (must) decide on measures and speed of steps here.

What helps parents to "let go" is described in Chapter 4.

Another difficulty for the parent-child relationship in adolescence is the role of the parents in supporting the child in the best possible way. This task is socially mediated. This is brought to parents from the beginning onwards and is ambivalent for them. The parents should accept their child as it is. At the same time, they should make sure that the youngster changes and becomes as normal as possible.

This means further pressure on those responsible. A child should function as inconspicuously as possible in society. For example, it is embarrassing for everyone, when a child suddenly shouts in public. In case of a small child, this behaviour is still accepted, but not in case of a disabled juvenile. How much (unobserved) experimentation can be tolerated in public? "Negative reactions of e.g. relatives or the public can intensify the bond of a family, so that a great intimacy in the familial relationship arises (..) and the child is additionally held in his dependent and autonomous role as a disabled person. [29]

“What is acceptable and in what situation?” This is not easy, because adolescents need challenges that are always associated with risks. However, because of their limitations, young people are often less able to protect themselves from injuries. Overstraining threatens to setback the development. This can go so far that the world out there seems too dangerous to these youngsters and this binds them even closer to the parents. However, borderline experiences are also important. If the developmental task of detachment is permanently postponed to later, it will get harder. The external incentives then must become even stronger. [30]

In this process young people have to experience many of their own fears as they are usually very much aware of the fears of their environment, especially of their parents. Such fears are often inaccessible, but still noticeable. This makes young people even more worried, especially when they fear losing their parental support. Therefore, if the desire for your own life threatens the relationship with the parents too much, it must be warded off. The easiest solution for this is also a closer bond with the parents; the dependency is reinforced. [31]

It could be helpful to talk to your child about your fears as well as theirs, and to encourage them to discover the world "on their own".

Please find additional information in the Communication module.

Further information on support can be found in chapters 3.1. and 3.3.

ACTIVITY: "Mobility Training"

Together with your child, create directions to a specific location. Read this for guidance: Mobility training

Photo: Pixabay.com